Major Marc Latta Focuses on Transformation

Longtime PA Navigates Life Shifts While Building an Organization to Help Other African American Men on Their Own Journeys

August 11, 2023

By Jennifer Walker

Major Marc Latta, DHSc, PA-C, has a favorite quote from abolitionist leader Frederick Douglass: “It’s easier to build strong children than to fix broken men.”

Latta’s professional life has been bookended by doing both. He began his career building strong children as an eighth-grade science and health teacher in his hometown of Hillsborough, North Carolina, and he will help fix the sociocultural traumas endured by African American men by creating safe spaces for them to connect and grow through his new organization, Elevated Black Man, LLC.

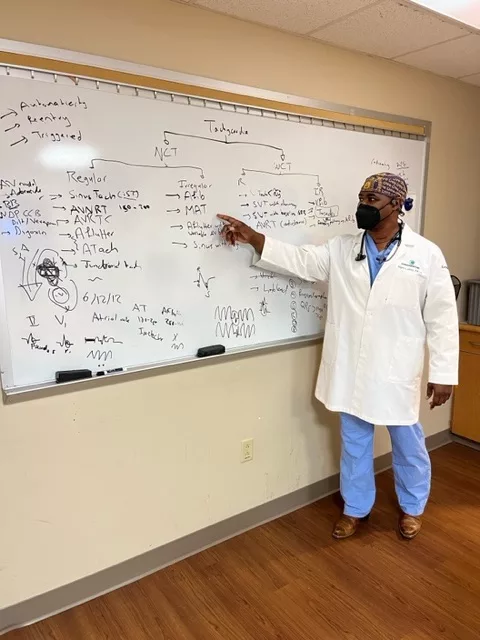

In between, Latta has spent 26 years as a PA specializing in cardiac surgery, education, and aviation medicine. He currently practices at Christiana Care Hospital in Newark, Delaware, and has been a medical officer with the National Guard of the United States Armed Forces for more than two decades.

[Stay connected to your PA community – join or renew your membership today]

Latta’s long and varied career as a PA and an educator is a direction he didn’t anticipate when he was a young kid expecting to follow in his grandfather’s footsteps and as a tobacco farmer in his hometown. His father taught him the value of hard work and suggested he explore a different occupation. This advice put Latta on a path that ultimately led to a career as a PA, and this experience is his motivation for wanting to help other African American men on their own journeys through Elevated Black Man, LLC.

“My venture now is purely looking at creating that environment—an anti-racist, safe space where men are seen; an environment that encourages transparency and vulnerability—because manhood is truly transformational,” he says.

Stumbling on the PA Profession

Latta was first introduced to the PA profession in the mid-1990s, when he was enrolled in a PhD program at Duke University to study biohazard science with a concentration in infectious disease epidemiology.

As part of this program, Latta did his thesis on bloodborne pathogens in the operating room, focusing on general, neurologic, and orthopedic surgery at Duke University Medical Center. He created a checklist for staff, ranging from the surgeon to the cleaning crew, that included all of the factors that could make them vulnerable at work to contracting a bloodborne virus.

One day a PA got stuck with a needle. Latta had to create a new line in the personnel column on his checklist and track this PA to make sure she didn’t develop a virus. In the process, he noticed the breadth of medical procedures that PAs are able to perform and how easily they can move between specialties. This excited him.

In 1995, Latta finished his master’s degree in infectious disease epidemiology, then left his PhD program after his acceptance to the PA program at the Duke University School of Medicine. He graduated in 1997 and was accepted into a 15-month general surgery residency for PAs at Montefiore Medical Center in Bronx, New York.

[Learn more about how PAs Go Beyond]

Cardiac Surgery: Developing a Specialty

Latta has practiced in cardiac surgery in New York, Virginia, and New Jersey. Then in 2015, he became a cardiac surgery and critical care PA at Christiana Care Health System in Delaware. Here, Latta rotated through every department involved in cardiac surgery—the operating room (OR), the ICU, and the step-down unit—which allowed him to provide care both during the actual surgery as well as during recovery.

“This is the first hospital where I was able to put everything together,” says Latta, who had previously practiced almost solely in ORs. “The hospital trusts us enough to not only take care of patients, but to perform bedside procedures. It’s a lot of responsibility.”

Latta planned to work in cardiac surgery until 2028, the year he would turn 58. But in 2020, an injury derailed his plans. He developed carpal tunnel syndrome in his left hand, and a mishap with his surgery left him without tactile and protective sensation in his left thumb and forefinger.

“We’re working with such fine suture in such a delicate area,” he says. “I just didn’t trust myself in the OR with cardiac surgery. It was a really trying time in my life because I trained in residency and worked my way up and was doing really well. To imagine not operating again, it hurt.”

Latta turned in his full-time resignation at Christiana in 2020, but he still works at the hospital, taking four, 24-hour shifts in the cardiac ICU per month.

He also continues to practice as an aviation medicine PA in the U.S. Army Medical Department. Latta is assigned to the Joint Force Headquarters Medical Readiness Detachment, and primarily supports Det 1 Company C, 1st Battalion (medical evacuation) 126th Aviation Regiment; and Company A, 3rd Battalion, 238th Aviation Regiments of the Delaware Army National Guard. He is responsible for the healthcare of approximately 75 aviation crewmembers—pilots, crew chiefs, flight medics, and mechanics—for one weekend a month and two weeks in the summer. He often answers calls, texts, and emails when not on duty.

U.S. Army National Guard: Nurturing Relationships

In 2001, Latta was the clinical coordinator for the PA program at Eastern Virginia Medical School (EVMS), and he invited the Army National Guard to speak to his students about joining their ranks as PAs. Although the opportunity wasn’t right for him at the time, he thought it might be a fit for some of his students. Then September 11th happened.

“That just dug into me,” Latta says. “Within a week, I contacted that recruiter and asked, ‘Do you have room for me?’”

On January 2, 2002, Latta was commissioned as a First Lieutenant with the U.S. Armed Forces in the Virginia Army National Guard. He spent three years on the medical detachment team, then transferred to aviation medicine in 2005.

Since then, Latta—now a Major who has completed all military professional development needed to be promoted to Lieutenant Colonel this summer—has been a primary care provider for his unit’s aviation crewmembers, treating illnesses while they are on duty or sending them to a higher level of care if needed. “My primary responsibility is keeping my crewmembers safe,” Latta says.

Traditionally, crewmembers might avoid a provider if they have a medical issue because they don’t want to get a Duty Not Involving/Including Flying rating, which would prevent them from flying for a length of time. Latta has found that having an open line of communication with each crewmember is the best way to address this challenge.

“I fly a lot with my aviators because I want to develop that trust with them,” he says. “Now if they have the common cold or the sniffles, they don’t run from me. These helicopters cost a lot of money, but a soldier’s life is even more important than the equipment. So developing that relationship is everything to me.”

The fact that Latta has been the primary medical provider for two aviation regiments for three years now is illustrative of how highly regarded PAs are today. “That shows the beauty of being a PA and how trusted we are in this game,” he says. “It’s amazing the things that our training allows us to do.”

Elevated Black Man, LLC: Addressing Sociocultural Traumatology

In 2015, Latta the father of three boys, ages 15, 11, and 9, began thinking about the trauma responses that people of color can have to societal events and personal interactions. This is when 17-year-old high school student Trayvon Martin was murdered by neighborhood watch captain George Zimmerman in Sanford, Florida.

“From a social justice standpoint, [the death of Trayvon Martin] opened the world to a whole lot,” Latta says. “This was the start of my thoughts on sociocultural traumatology. It’s not talked about often, but it’s experienced daily by marginalized or oppressed people. Children’s responses to trauma could be precipitated by biased treatment from parents, communities, or ethnic groups that they have experienced throughout the history of this country.”

When looking at African American students, for example, there are several ways to begin addressing traumas, including teaching emotional intelligence, adopting holistic admissions processes, and using language that will contribute to the success of students.

Emotional intelligence is how people manage their emotions when faced with challenges, conflict, or stress, and it’s something that Latta wishes he had been taught when he was younger. While in his PA program, Latta had a trauma response to being the only African American male. After classes, he chose to regroup by spending time alone rather than participate in study groups that could have had a positive impact on his grades during his didactic year.

“Culturally, I had to get away from the masses to come back to myself,” he says. “And that was probably the biggest mistake I made. If I had some emotional intelligence, I would have found a way around that.”

Latta also feels that PA programs and schools in general can create safe spaces for African American students by adopting holistic admissions processes. This would involve taking into account the whole student—for example, whether they were raised in a medically-underserved area or if they are the first generation to go to college—instead of only looking at test scores and grades. This practice would help ensure that students have peers who look like them.

Latta will take the next step in addressing sociocultural traumatology in adults through Elevated Black Man, LLC, which he founded in January 2023.

“We’re creating anti-racist spaces for us to be vulnerable so that African American men can talk, and we can explore being able to play out our emotions in healthy commune with other men who look like us and are experiencing the same daily life situations,” Latta says. He plans to create these spaces by connecting with adult male identifiers, regardless of sexuality, to offer workshops, lectures, master classes, one-on-one men’s intensives, and coaching, and by creating adventure weekends for men.

Looking forward, Latta plans to return to teaching in the future—after leaving full-time cardiac surgery, he spent two years as the academic education director of the developing PA program at Meharry Medical College in Nashville, Tennessee—while continuing to pursue his passion and purpose in men’s work.

Reflecting on his own journey, Latta says, “I get to do things for me now. I’ve been checking these boxes because society told me that as a man, I’m supposed to be tough, to be successful, to not cry, to have degrees, to do this, to do that. But society didn’t teach me that there’s still me behind all of that, and now I get to reimagine manhood. So I’m enjoying this part of my life.”

Jennifer Walker is a freelance writer in Baltimore, MD. Contact Jennifer at [email protected].

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in February 2023.

You May Also Like

Kathryn Reed Makes Her Mark on the PA Profession

From Practicing in War Zones to Remote Islands, Melinda Rawcliffe Finds Endless Opportunities as a PA

When It Comes to Leadership, Gerald Kayingo Has Done It All

How a Helicopter Crew Chief and Bioterrorism Expert Ended Up a PA

Thank you for reading AAPA’s News Central

You have 2 articles left this month. Create a free account to read more stories, or become a member for more access to exclusive benefits! Already have an account? Log in.