From Practicing in War Zones to Remote Islands, Melinda Rawcliffe Finds Endless Opportunities as a PA

“I Love Every Bit of What I’ve Gotten to Do.”

By Jennifer Walker

October 6, 2022

Melinda Rawcliffe’s experiences as a PA have been varied, but she sees a common thread in her work: “What I enjoy most is being right in the middle of the disaster with patients, getting them stabilized, and getting them to the next level of care,” she says. This has been a theme in her career from when she got her first position as an EMT at age 19 and has continued into her contractual assignments as a PA. These assignments have taken her to the war zones of Iraq and Afghanistan, to the remote Alaskan island of Shemya, to oil rigs in the Arctic Circle, and more.

“PAs are designed to overcome adversity,” says Rawcliffe, MPAS, DMSc, PA-C, an adjunct professor at A.T. Still University in Mesa, Arizona, who now practices in emergency medicine in a rural mining community and volunteers in a Mexican clinic with the Flying Samaritans. “We’re generalists, so we can do everything from family medicine and emergency medicine to psychiatry and obstetrics. If you want a connecting factor in all of my work experiences, it’s because I’m a PA.”

[Stay connected to your PA community – join or renew your membership today]

Refining Her Interests in Healthcare

As a child, Rawcliffe was inspired by her grandfather, a general practitioner who also performed surgeries and deliveries at his clinic in the small town of Yuma, Arizona. So as a 19-year-old, when Rawcliffe was trying to decide what to do for her career, her grandfather said, “Go take an EMT class and find out if you can even stand the sight of blood.” Rawcliffe did that, and she loved it.

Rawcliffe had to wait until she was 21 to get insured to drive an ambulance, so she spent two years working as a medical assistant before joining a Basic Life Support ambulance crew, where she was one of two EMTs on the vehicle. “I loved being in the field, I loved going into people’s homes, I loved seeing them at their moment of crisis and trying to help,” she says.

But Rawcliffe, who was also a young mother at the time, began to feel the strain of balancing her 24-hour shifts with being a parent. Her mom, who was an accountant, suggested she get into the business side of medicine. So Rawcliffe started a consulting company where she supported physicians in managing their books and hiring their staff. “But this wasn’t really where I wanted to be,” says Rawcliffe, who had her consulting business for 10 years. “I wanted to be in patient care.”

At her grandfather’s suggestion, Rawcliffe looked into the PA profession, then enrolled in the PA program at A.T. Still University in 2005. “I felt like I found my calling in life for the first time,” she says. “Here I am in my mid-30s and a single mom and excited for this new career.” After graduation, Rawcliffe gravitated toward emergency medicine because of her background as an EMT, and she practiced at Casa Grande Hospital for three years.

Then, in 2011, a friend who had been deployed in Afghanistan approached Rawcliffe with a suggestion: She could look into pursuing overseas medical contract work with DynCorp International, a company that placed contractors with U.S. personnel. Rawcliffe has family who served with the U.S. Army, and her husband and her daughter both serve with the U.S. Air Force. Shortly before starting her PA program, Rawcliffe had been contemplating joining them as a flight medic, but unfortunately was unable to do so.

“My friend said, ‘There’s a lot of contractors over here in the Middle East. You can still serve without going into the military,’” she says.

Rawcliffe’s first assignment was in Baghdad, Iraq, where she worked on the armored compound of a Kurdish special forces general as the Chief Medical Officer overseeing 12 paramedics and providing care for more than 100 multinational personnel. “I had not really been out of the country before except to Mexico,” she says. “So here I go with my passport, trucking it overseas.”

Providing Care in War-Torn Regions

In 2011, the Green Zone, a four-mile, heavily fortified and primarily U.S.-occupied area in Central Baghdad, was breaking up, with the United States eliminating much of their military and contractor presence in the region. DynCorp, which was later acquired by Amentum in 2020, had contracted a small portion of the Kurdish general’s armored compound to continue to offer its private security detail (PSD) services. This is where Rawcliffe was stationed.

It was a 96-hour trip from her home in Arizona to the compound in Baghdad, which included several nerve-wracking hours of waiting for her PSD team at the airport for transport. Once she arrived and placed her bags on the bunk bed in her chilly room, she had second thoughts. “There’s no heat in the middle of December, I’m freezing to death, and I haven’t showered in four days,” she says. “I sat on my bed and thought, ‘What have I done?’”

But Rawcliffe quickly settled into a routine. Along with the paramedics she managed, she was responsible for providing medical care while safely moving PAXs – the term used to describe the people being protected and transported – around high-threat locations in the region. “We would safely get them from the place where they were living to the place that they worked every day and back again. That was our entire mission,” she says.

The healthcare team also had a small clinic in the compound that was made of Conex boxes stacked side by side. They had a trauma area, a small exam room, a small pharmacy, and an open area, and here they attended to the healthcare needs of the PAXs support team, which included everything from routine care to traumas and injuries.

After her assignment in Baghdad, Rawcliffe went on to serve in Kabul, Afghanistan, for 13 months as part of a PSD team on a much larger base. Here, in addition to safely transporting U.S. representatives to their missions, she also provided care for several groups within the same building, including lawyers who were doing advisory missions; agents from the FBI, MI6, DEA, and the U.S. Marshals Service; and a group of Nepalese contractors who did static security for DynCorp.

“I made great friends,” she says about these assignments. “Here I am, this little farm girl from Gilbert, Arizona, and I’m globetrotting and doing private security details and tactical weapons training. If anybody ever said I was going to do this when I grew up, I would have laughed at them. But I love it.”

Taking Assignments in Remote and Austere Environments

In 2014, Rawcliffe spent a year in Shemya, an island that is located at the tip of the Alaskan Aleutian island chain, about 1,200 miles from Anchorage and 200 miles from the coast of Russia. There are old missile silos here, left over from when the island was a missile launch location in the 1970s. Today, Shemya is home to Eareckson Air Station, a U.S. military airport, which has a long runway the military uses for emergency evacuations. About 250 people, all of whom are from other places, live on the island, which is about two miles wide and four miles long.

On assignment with Remote Medical International (RMI), Rawcliffe was one of two PAs in Shemya who were stationed in an old World War II-era building that had so much mold in it, “it looked like carpet,” she says. Rawcliffe and her colleague were the only medical staff on the island, where it sometimes took them 24 hours or longer to evacuate patients who had more serious issues and needed further care.

Rawcliffe remembers a 70-year-old patient who had limited mobility on his left side due to a previous stroke. “I just kept thinking to myself, ‘If he has a heart attack or another stroke, he’s going to die out here,’” Rawcliffe says. “Because there’s no way I’m going to be able to get him out of here before things go badly south. You have to be prepared to hold your emergent patient for a day, sometimes longer. Everybody out there on the island knew living there was a calculated risk for this reason.”

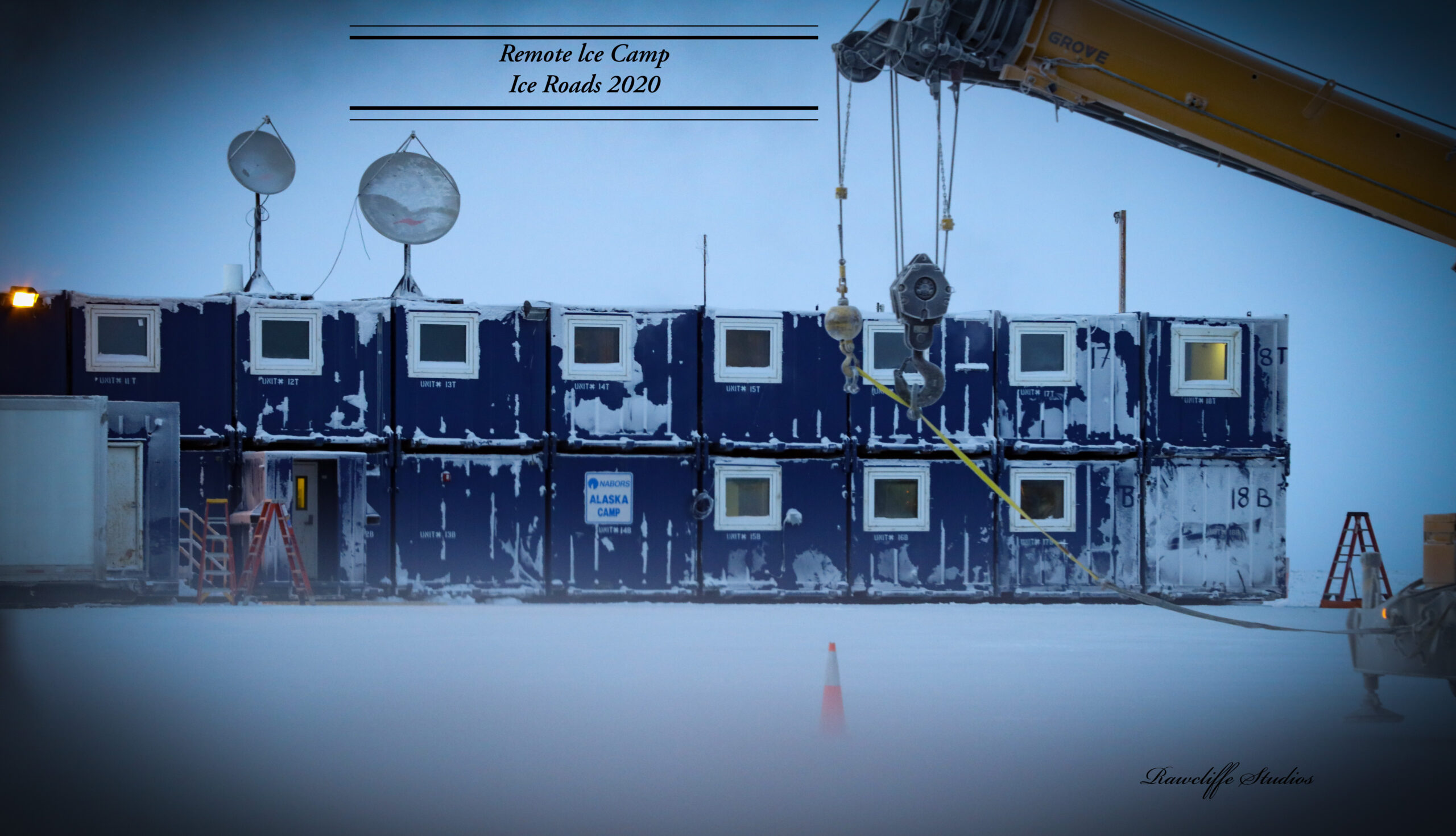

Then, in January 2020, Rawcliffe went to another remote environment: the Arctic Circle. She was on assignment with Fairweather to provide medical care in an oil field that was owned by ConocoPhillips, a company doing exploratory oil drilling in Alaska. This was the second time that she worked on oil rigs in the Arctic Circle, having spent the summer of 2015 on a similar assignment. “The Arctic Circle is no joke. It was negative 87 degrees most days, so the weather is constantly trying to kill you,” says Rawcliffe, adding that the silver lining of these extreme temperatures was that it was amazing to see the local wildlife, including Arctic foxes, ptarmigans, and caribou.

In this region of Alaska, ice roads connect the drilling sites, and a 30-person team on Rawcliffe’s road crew was responsible for building these roads for the oil rigs while respecting the land and the local population. Rawcliffe was the sole provider for her crew and surrounding rig crews, and her clinic was located in the front half of her bedroom at Ice Camp, the building where her crew lived. Along with routine medical care, many of her patients also needed emotional support due to the remote nature of the job and the separation from family.

“You’re two days travel away from the closest thing that resembles a small ice airfield that can get you home,” she says. “You can’t just leave and go take care of family issues. There was some amount of emotional support needed more than anything else.”

Then, while Rawcliffe was still on this assignment, COVID-19 hit. “All the air traffic stopped, and nobody was allowed to come into or out of the camp for two weeks,” she says. “We were captive up there on the ice.” Rawcliffe became the Chief Medical Officer for the 10-member COVID response team, which needed to develop a plan for hundreds of ConocoPhillips’ employees that were stationed on multiple oil rigs in the region. The crews resided in dormitory-style living spaces, so Rawcliffe and the team worked 18 hours a day to put procedures in place that laid out how to isolate a crew member who tested positive, and how to keep the virus from spreading in close quarters.

“I thought I was going to be dealing with people with acute appendicitis and bad work injuries and traumas, and somebody handed me an international pandemic with no precedents and very little resources,” she says. “It was the most stressful time of my life, trying to sort out how to be responsible for 500 lives for a major corporation that was very risk adverse.”

Practicing in Rural Environments and with Volunteer Groups

Rawcliffe has also worked in rural healthcare in her home state of Arizona. In 2013, after she left Afghanistan, she spent a year working in emergency medicine in the small ranching town of Wickenberg. Rawcliffe was the only provider in an eight-bed emergency room at Wickenberg Community Hospital, which did not have any specialists on staff. She cared for patients with a variety of ailments, including rattlesnake bites, gunshot wounds, and cases of dehydration, the result of cattle ranchers and gold miners spending too much time in the sun. She also organized further treatment at a larger hospital that was accessible by helicopter for patients who needed care beyond emergency and inpatient services.

And today, Rawcliffe is back in Arizona, practicing in emergency medicine at Mt. Graham Regional Medical Center, a rural critical access hospital in the town of Safford, which is known for its copper and gold mining industries. Mt. Graham offers a variety of services, from a cancer center and a sleep center to gastrointestinal care, a maternity ward, and an intensive care unit. Rawcliffe is one of 12 providers in the emergency room at the hospital, where she often handles high-acuity cases due to a lack of physicians in the area. She also precepts students from across the state of Arizona, who often come to the hospital for their rural rotations.

This position also marks a turning point for Rawcliffe and her husband, David. “We’re starting to slow down,” says Rawcliffe, adding that David now works in the mining community after 35 years of full-time service in the U.S. Air Force.

However, Rawcliffe continues to go on short assignments through her volunteer work with the Flying Samaritans, a group she has been a member of since 2013. The Flying Samaritan’s Phoenix chapter has a small free clinic in a former cannery building in Adolfo López Mateos, Mexico, that has been in operation for 30 years. Here, the volunteer team offers medical, dental, and chiropractic services.

“We mostly see family medicine cases: chronic hypertension, diabetes, rashes, joint paint,” says Rawcliffe, who also volunteers as a member of the AZ-1 DMAT team with the Federal National Disaster Management Services, a new role that has taken her to Indianapolis, Indiana, and Syracuse, New York, to provide medical care after natural disasters.

To get to the Flying Samaritans’ clinic, each member of the volunteer team flies with a volunteer pilot, and the two split the cost of fuel. The teams land on a dirt landing strip near a small hotel in Mulegé on Friday night, then fly out to Adolfo López Mateos on Saturday morning for the clinic. Rawcliffe and the other providers see a combined 200 to 300 patients on Saturdays before returning home to Arizona on Sunday. The team travels to the clinic every month between October and July, and Rawcliffe goes to the clinic seven to eight times per year.

“I love to do medical mission work as I believe that this informs others around the world about PAs and what we do,” says Rawcliffe, who has also served as the state president for the Arizona State Association of Physician Assistants (ASAPA) and has been ASAPA’s elected representative to the AAPA House of Delegates since 2017 and a member of the AAPA Standing Rules Committee.

Challenges and Advice for Other PAs

Each of Rawcliffe’s varied assignments have come with their own challenges. Medical supplies were very limited in all of her international experiences. “You have a blood pressure cuff, a stethoscope, and, if you’re lucky, a urine dipstick,” says Rawcliffe, who is passionate about whole-person healthcare, home care and aging in place, and removing barriers to care. “But my grandfather always harped on me about having good exam skills, about having a gut instinct, about not being so reliant upon lab tests and radiology. That was his philosophy, so I was comfortable in those scenarios.”

On a personal level, being away from family for months at a time with limited opportunities to come home was difficult. “Your family has to be very supportive of you doing this, and my husband was,” says Rawcliffe, whose daughter was 18 when she went on her first mission. “He’s military and he grew up in a military family, so he understood the challenges and what this work was going to do to our relationship. I don’t think I could have done it with anybody else.”

For PAs who are interested in pursuing a similar path, Rawcliffe advises that they be open to different experiences and they don’t let fear hold them back. “Every single time I got on a plane to go someplace, I had butterflies in my stomach because I didn’t know what I was getting myself into,” she says. “But I still did it. I’ve gotten to go to different cultures and learn about their challenges, their family dynamics, their belief systems, their morals and ethics, and their religious outlooks on life. And I feel like I have grown as a person medically, culturally, and emotionally by having those experiences. I love every bit of what I’ve gotten to do.”

Jennifer Walker is a freelance writer in Baltimore, MD. Contact Jennifer at [email protected]

You May Also Like

Wanderlust Lessons: Advice from Travel Medicine PAs

PAs Respond in El Paso Shooting Aftermath

PA Julie Mueller Thrives in Remote Antarctica

Emergency Medicine PA Braves Alaskan Tundra to Lead Iditarod Race Medical Team

Thank you for reading AAPA’s News Central

You have 2 articles left this month. Create a free account to read more stories, or become a member for more access to exclusive benefits! Already have an account? Log in.