PA Students: Enhance Your Study Strategy to Maximize Learning

PA Educator Shares the Science Behind Memory

September 1, 2023

By Kristopher R. Maday, MS, PA-C, DFAAPA

School is all about memory. You are presented information in class, and you try to remember everything the professor is saying in order to transcribe what you think is important on your notes. Then you go home and study these notes, textbook chapters, and journal articles to make sense of the material. This is where our cognitive weapons of choice come out: different colored highlighters, index cards, sticky notes – all in the hopes that it is processed into neat little compartments in your brain so you can recall them for the exam. Rinse, wash, repeat – for more than two years of PA school. But what is the science behind memory, and why do some things work better than others?

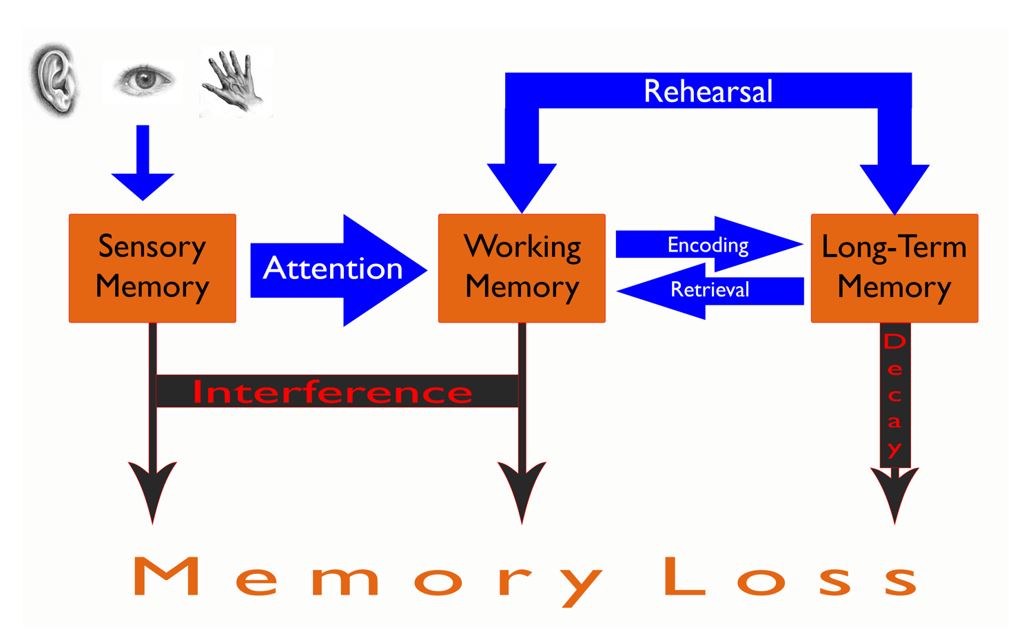

Most people think of memory as just short-term and long-term, but, depending on which psychologic theory of memory you prescribe to, there can be many more. I, personally and professionally, like the three-tiered, information processing model to memory: sensory, working, and long-term.

[AAPA Student Members: Access Your Exclusive Picmonic Benefit]

Sensory Memory

The first step in memory involves the processing of sensory stimuli that are introduced in the learning environment. The brain uses three main senses (sight, sound, and touch) to get as much information brought in as possible. Now, if you had to process every single sensory stimulus into your working memory, your brain would get overloaded in a matter of seconds. To avoid this, you use sensory memory as the environmental buffer to pick and choose what you think is the most important – this is where attention comes in. Attention is the filter from the sensory memory system into the working memory system and allows us to focus on smaller, more important sensory stimuli.

Attention is the bodyguard who stands outside of the “Working Memory” club. He will pick and choose what information gets through for further processing to make sure the club doesn’t get overcrowded.

Working Memory

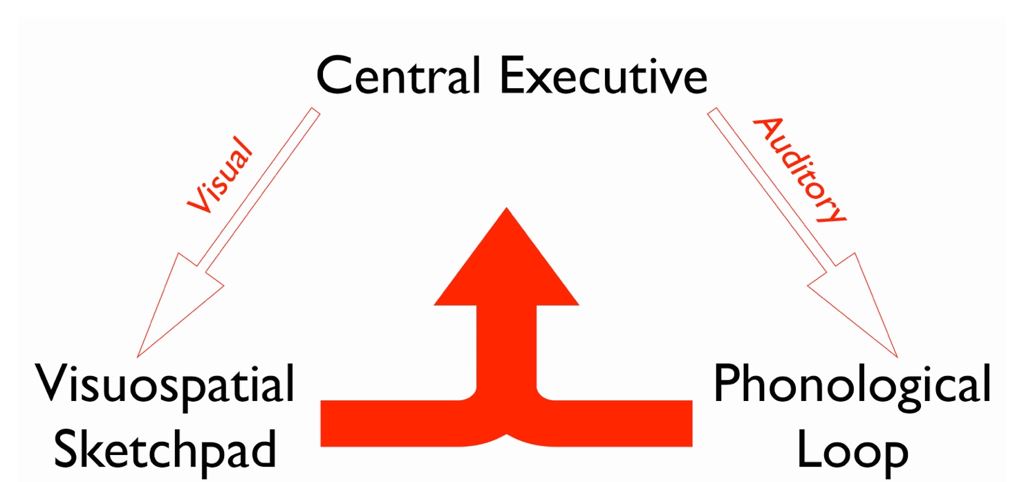

Once the sensory information is attended to, we can store it in a temporary cognitive sandbox where we can actually work with it. This is your working memory. It is short (15-30 seconds) and the information stored here only stays if the learner is actually doing something with it (rehearsal). There are three main components of working memory: central executive (supervisor), the phonological loop (language storage), the visuospatial sketchpad (visual storage). As you hear and see things over and over again, you start to make connections and see correlation between the information and begin to encode it all into neat data packages. Each system is different, and the cognitive load when using both systems is only slightly higher than using them individually. Cognitive psychologists recommend using this to your advantage while studying. For example, assign each class a room in your house and only study in this room. It will increase the likelihood of correctly recalling the information when you can get your cognitive bearings straight on the location you learned the information. You can incorporate similar strategies, such as listening to different music or artists for different subjects.

The more you rehearse this information in working memory, the greater the cognitive load. But it will also increase the likelihood that the information will make it to long-term memory.

Long-term Memory

Due to this increased cognitive load of working memory, it is not possible to keep information in working memory indefinitely. This is where long-term memory comes into play. We try to categorize this information into packages for easy storage and recall in long-term memory. There are three steps to this process: encoding, storage, and retrieval/rehearsal. The majority of the energy used when studying is trying to encode the information in working memory so it can be efficiently and effortlessly recalled when needed. This is why mnemonics, acronyms, and all the other things we do as PA students help process and package new information so we can remember it later. “Oh Oh Oh To Touch And Feel Very Good Velvet, Ahhhh” may mean nothing to you, but it is how I can still recall all 12 cranial nerves to this day.

[Study Less, Remember More: A Free Webinar About Memory]

Loss of Memory

Even with all these sophisticated and complicated cognitive pathways that our brains have developed to retain information, we still forget and lose information. There are many theories behind this, but the two main ones I like are: information decay (the less you use it, the less you can recall) and interference (learning new information inhibits recall of old information).

To limit interference when I am teaching, I try not to overload the senses with extraneous stimuli. If I stand up and just read the PowerPoint (which is not teaching by the way), you (the student) can’t listen to what I am saying when you are being bombarded with paragraphs of text that you feel compelled to read. This leads to overload of the sensory and working memory as you are trying to listen, read, and process everything that is being thrown at you.

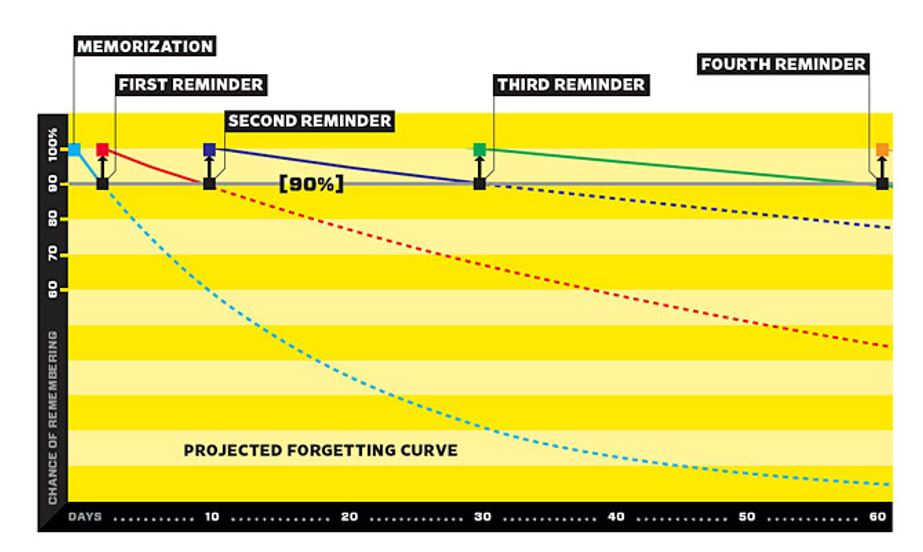

To limit long-term memory decay, I utilize spaced repetition. When I am teaching, I like to bring up old information (last exam, last semester, etc.) to re-introduce to it to my students. It is also why I believe in comprehensive final examinations. It gives them an opportunity to dust off the stored information in long-term memory and play with it again in the sandbox of working memory. This strategy has been shown to improve retention and efficiency of recall when you need it the most – when taking care of patients.

[Read: Surviving Your Didactic Phase]

This is part of a series on memory, learning, and medicine. The next article will focus on cognitive load and how this comes into play in PA school, as well as clinical practice. Look for it in September.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published on August 26, 2020.

References

1) Anderson JR. Cognitive psychology and its implications. 7th ed. Worth Publishers. 2009

2) McLeod SA. Working Memory | Simply Psychology. Available at: http://www.simplypsychology.org/working memory.html. Accessed February 15, 2016.

3) Cognition (Sensory memory). Introduction to Instructional Design. Available at: http://byuipt.net/564/2013/08/23/cognition-sensory-memory/. Accessed February 15, 2016

4) Baddeley AD. Working memory. Science. 1992;255:556-559.

5) Cognition (Long-term memory). Introduction to Instructional Design. Available at: http://byuipt.net/564/2013/08/23/cognition-long-term-memory/. Accessed February 15, 2016.

6) Wolf G. Want to Remember Everything You’ll Ever Learn? Surrender to This Algorithm. Wired.com. Available at: http://www.wired.com/2008/04/ff-wozniak/?currentpage=all. Accessed February 15, 2016.

7)Nickson C. Learning by Spaced Repetition. Life in the Fast Lane Medical Blog 2011. Available at: http://lifeinthefastlane.com/learning-by-spaced-repetition/. Accessed February 15, 2016

Kristopher R. Maday, MS, PA-C, DFAAPA is Associate Professor and Program Director in the PA Program at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center in Memphis, Tennessee. Contact him at [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter @PA_Maday.

You May Also Like

How to Stay on Track in PA School During a Global Pandemic

5 Mental Health Tips for PA Students

The Ups and Downs of My First Year as a PA

Thank you for reading AAPA’s News Central

You have 2 articles left this month. Create a free account to read more stories, or become a member for more access to exclusive benefits! Already have an account? Log in.