PA Katherine ‘Kaesa’ GeeBah Footracer Believes Healthcare Can Make the World a More Equitable Place

In Her Clinical and Volunteer Work, Footracer Strives to Advance the PA Profession and Improve Access to Care

November 17, 2022

By Jennifer Walker

In May 2020, Katherine “Kaesa” GeeBah Footracer, MS, PA-C, volunteered with the Indian Health Service (IHS) in Kayenta, Arizona, a community that is part of the Navajo Nation, the largest Indian reservation in the United States. After reading about the severe impact of COVID-19 on communities in the Navajo Nation – which consists of about 25,000 miles of land across Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah – Footracer, a member of the Navajo Nation by birth who grew up in Los Angeles, looked up a contact at the IHS and sent in her resume. She used her vacation time for the trip and spent two weeks in an influenza-like illness clinic in the emergency department in the Kayenta Service Unit. There, a reservation-wide curfew was in effect from Friday through Monday at the time, making the community seem very isolated, she says.

At the clinic, which housed the only pharmacy in town and carried a limited formulary, Footracer treated patients whose chronic illnesses were more advanced than she typically saw among her patient population in California, particularly in the case of diabetes, which is rampant among the Navajo Nation and most American Indian groups.

“There’s so many factors that go into that,” says Footracer, whose presence at the Kayenta clinic also allowed the regular clinicians to take a break from their usually packed schedules. “Some places don’t have electricity or running water, so if you’re on insulin, where do you keep it? It’s harder to keep healthy food because the nearest grocery store may be an hour away and people might not necessarily have a fridge to store fresh food or transportation to get to the market. People have a long history of distrust of the government for good reason. And then there’s the fact that the Indian Health Service is so deeply and chronically underfunded, and they could probably use twice the number of clinicians.”

Although Footracer has made several visits to the Navajo Reservation where her dad grew up and some of her relatives still live, she does not have a strong connection to that environment. But whether she’s volunteering at a clinic on a reservation or providing care at an urban healthcare facility in Los Angeles, these types of experiences have shaped one of her core beliefs: Footracer sees primary care as an “act of social justice.”

“When people don’t have adequate health care, they can’t live to their fullest and they can’t achieve what they’re capable of,” says Footracer, who currently practices in the Department of Family Medicine at the University of Southern California (USC) and has been involved in many leadership opportunities to advance the PA profession and improve healthcare access. “So they suffer, their families suffer, their community suffers, and the world suffers. Healthcare is so important for getting our world to a more equitable place.”

A Winding Path to Becoming a PA

Footracer has had some personal experience with inequalities in healthcare. Both of her grandmothers were diagnosed with diabetes. Her dad’s mom, who lived on the Navajo Reservation and who had inadequate healthcare, died in her 60s from gangrene in her leg, which was secondary to her diabetes diagnosis. Her mom’s mom, who lived in an upper middle-class neighborhood in LA where there were a number of hospitals and clinicians within easy access, lived to be 98.

“That’s what a healthcare disparity looks like: a 30-year difference in lifespan,” she says.

Footracer has always believed in doing work that is meaningful, but it took more than a decade for her to find healthcare as a career. She did gain some experience in the field while in college in the early 1990s. Then, Footracer’s friends urged her to take a first aid class, and Footracer was surprised to find that she loved it. She went on to work as an EMT full-time for a summer and part-time during the school year while still in college. When the 12-hour shifts became too grueling to balance with her course load, Footracer shifted to volunteering with the Red Cross, where she taught community CPR and basic and advanced first aid.

[Stay connected to your PA community – join or renew your membership today]

“I thought about med school at that time,” she says. “But honestly, I kind of got burned out. I wasn’t prepared emotionally for all of the issues that you see when you’re an EMT, so I put medicine on the back burner.”

Footracer graduated with degrees in psychology and dance, and worked in nonprofit arts management for eight years at organizations like the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra and Angels Gate Cultural Center. She learned a lot about organizational management, but she also grew further away from helping people as she advanced into higher positions. So in 2000, Footracer decided to go back to school to become a massage therapist.

Then, after a few years working at a spa, Footracer made a seemingly small decision that led to a pivotal shift in her career. She chose to take anatomy and physiology classes at her local community college simply because they seemed interesting and fun. At the end of her anatomy class, the teacher asked her if she needed a recommendation for medical school. Footracer was surprised because she hadn’t been thinking about a career change, but her teacher’s comment planted the seed.

Later, Footracer met one day with her lab partner who was planning to apply to a PA program, and she introduced Footracer to the profession. Footracer did some research and informational interviews and found that the PA profession was a good fit for her.

“I love the level at which we can work and I love the concept of professional lateral flexibility and how we can change specialties without having to return to school or do a fellowship,” she says. “It’s a unique profession in that way.”

After completing her prerequisites while continuing to work at the spa, Footracer moved across the country to attend Seton Hall University in South Orange, New Jersey, in 2005. Her three-year program had a research component, including a group thesis project. Footracer’s group focused on how alternative and complementary medicine practitioners felt about partnering with providers in allopathic medicine. They received more than 3,000 responses, and the final piece became a peer-reviewed, published article.

After graduating in 2008, Footracer spent two years working in urgent care at a private practice in New Jersey. But she missed California. So she moved back to LA in 2010 and practiced for a decade with a privately held HMO/ACO company. Then in 2021, she came to her current position at USC. There, Footracer had the opportunity to lead a new outdoor clinic, continuing with the leadership skills that she began to develop in her PA program.

Gravitating Toward Leadership Opportunities

At Seton Hall University, Footracer jumped on leadership opportunities to support the PA profession, and she held different positions during each of her three years there. She was the Seton Hall representative to AAPA’s Assembly of Representatives, a representative to the AAPA House of Delegates (HOD), and a member of a reference committee for the HOD.

Asked what attracted her to leadership roles, Footracer says, “I love the diversity of perspectives in the HOD. There’s so many layers to issues. I appreciate getting a better understanding of how different policies and guidelines can impact patient care and our profession in different fields and settings, and seeing the passion that people bring to the discussions.”

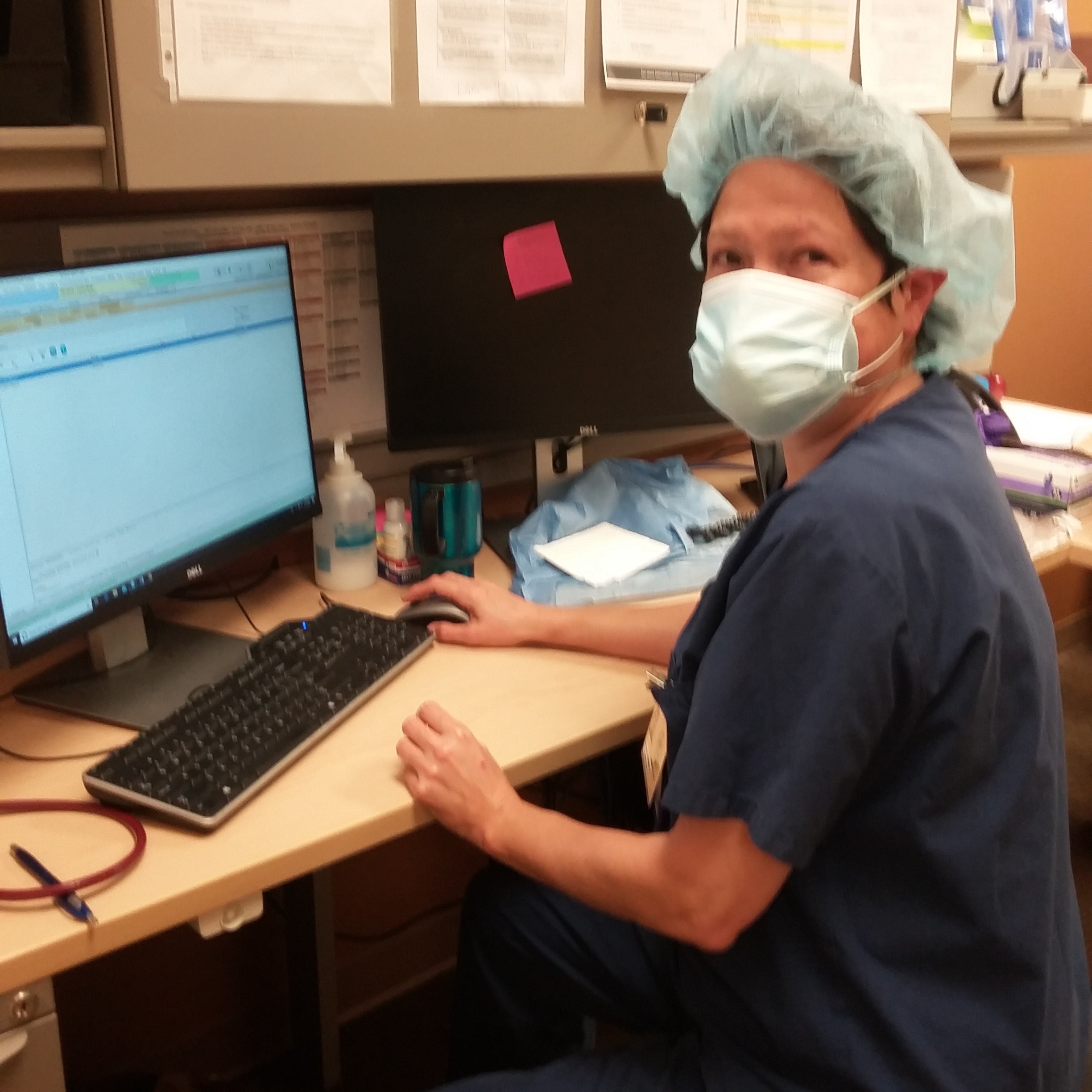

In her current role at USC, Footracer mainly sees adult patients. She performs physicals and preventive care exams, pre-operative evaluations, and hospital follow ups; manages chronic conditions; and treats acute ailments. But she was excited to take the lead on a new pilot project in November 2021: the COVID-Like Illness Outpatient Clinic. The goal of the project was to develop a space where patients who had COVID-like symptoms could get in-person treatment while preventing others from potentially being exposed to the virus.

“One of the problems we had with treating COVID is having a space where you can treat someone that doesn’t put other people at risk,” Footracer says. “Telemedicine helps to some degree, but it’s a lot harder to tell how sick somebody is through telemedicine. So we had this idea to set up a clinic space in the parking garage of one of the outpatient clinics.”

There, Footracer and her medical assistant had equipment and a computer on carts, and they had designated parking spots for patients. They met each patient at his or her car, where the medical assistant took vitals and Footracer performed exams. They saw up to 20 patients a day who were diagnosed with COVID, the flu, strep throat, and other respiratory illnesses. The clinic was open until March 2022, when COVID numbers began to decrease.

“This clinic really expanded what I thought we could do outdoors,” Footracer says. “I could listen to [patients’] lungs directly, I could look in their ears and their throats and do what I felt was a good, quality exam. Also, because we were outside, we could even do nebulizer treatments. I loved being able to help people like that without putting anyone else at risk. Patients really liked the convenience of it, too.”

Outside of her work, Footracer – who is also a member of the Los Angeles County Volunteer Disaster Surge Unit – has continued to take on volunteer leadership roles in professional organizations. She was a member of the AAPA House of Delegates for California and New Jersey and the AAPA Quality Care Workgroup, as well as a board member of the New Jersey State Society of PAs. She is currently the Chair of the Board of Directors for the National Commission on the Certification of PAs (NCCPA), which will launch PANRE-LA, a new longitudinal recertification exam option for PAs, in January 2023.

Footracer is passionate about getting other PAs involved in similar leadership opportunities. “I think a lot of people are afraid that they won’t know what to do or they don’t have the skills,” says Footracer, who continues to write and publish in peer-reviewed journals on a variety of topics, from the use of healthcare among immigrant populations to travel-related fevers. “But PAs expand their medical knowledge and their boundaries all the time, and we spend a lot of time developing new clinical skills. I hope more PAs will reach out of their comfort zones into non-medical areas and start exploring leadership.”

Jennifer Walker is a freelance writer in Baltimore, MD. Contact Jennifer at [email protected].

You Might Also Like

PA Featured on TODAY Show Will Return to Navajo Nation to Practice

Early Career PAs Share Leadership Advice

3 Ways PAs Can Advance Their Careers Through Leadership

Improving Access to Healthcare in Alaska’s Rural Villages

Thank you for reading AAPA’s News Central

You have 2 articles left this month. Create a free account to read more stories, or become a member for more access to exclusive benefits! Already have an account? Log in.