Barriers to Care: Four PAs Talk About Serving Rural Communities During the Pandemic

‘If It Weren’t for a PA Here, They Wouldn’t Have Access to Care Locally’

August 5, 2021

By Jennifer Walker

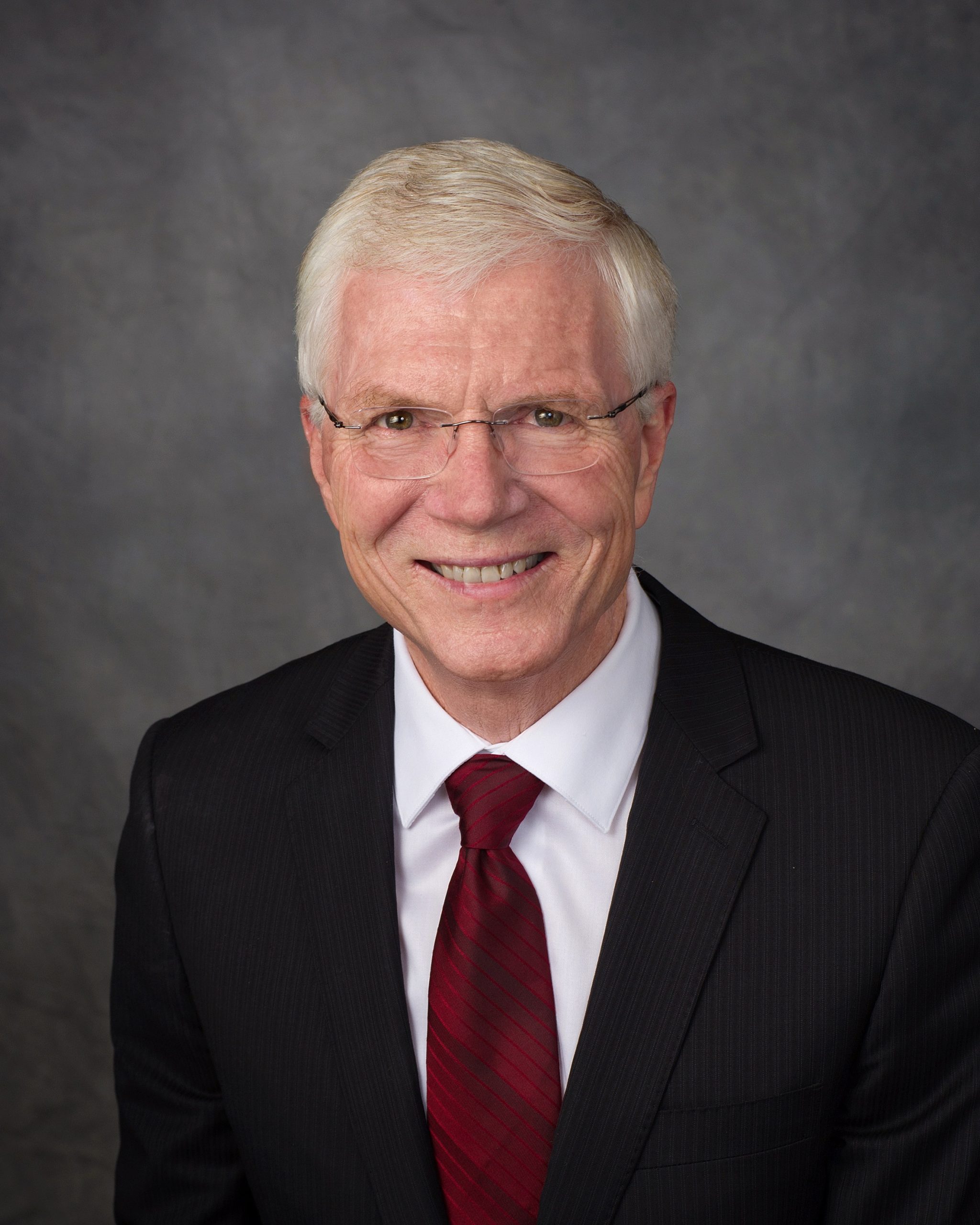

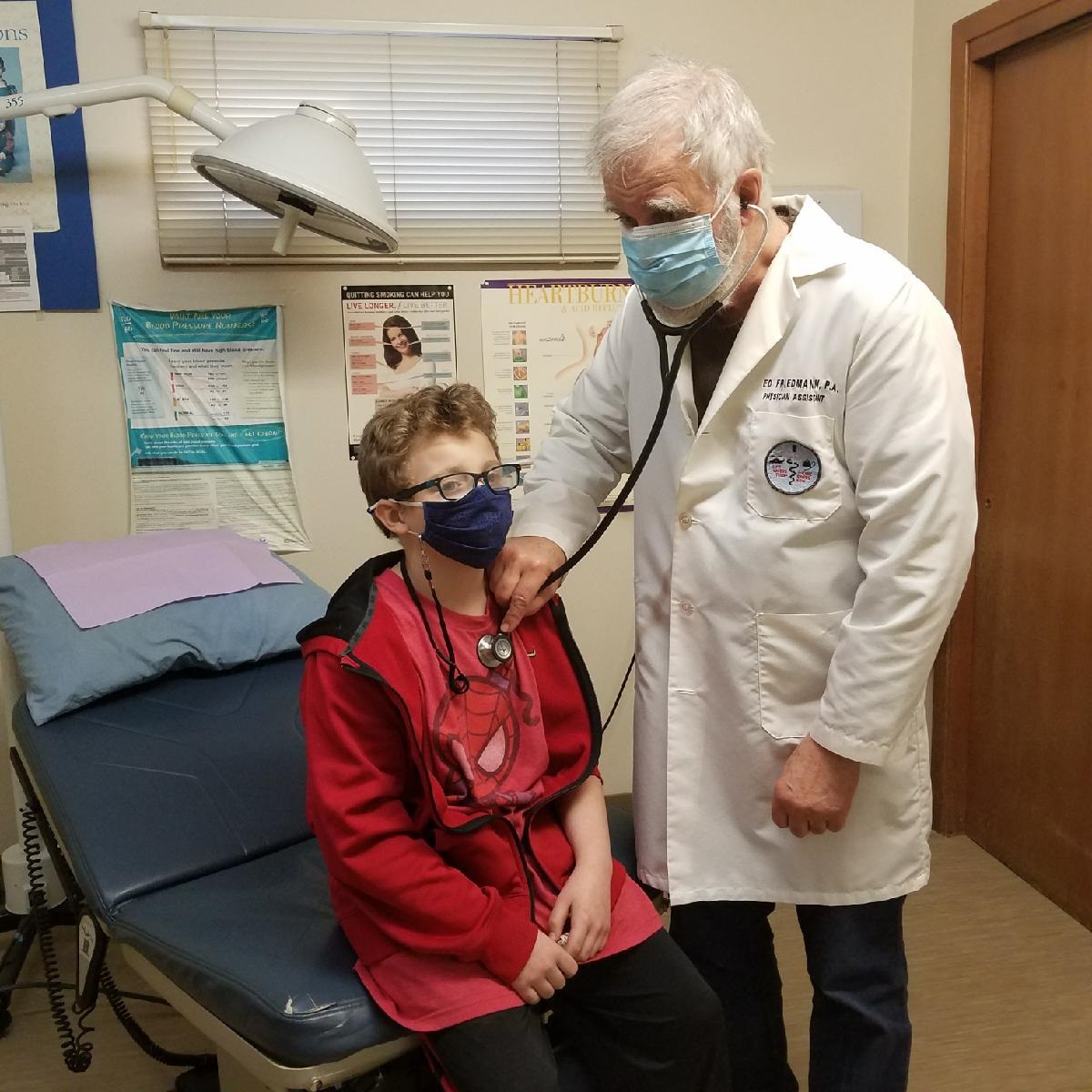

During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, Ed Friedmann, PA-C, DFAAPA, made some changes to how he provides patient care at his small community clinic in Redfield, Iowa. As the owner and sole provider at the Redfield Medical Clinic, which serves a community of 833 people, he changed his protocol for screening patients, hanging signs on the clinic doors instructing them to call before entering the building and even making “car visits.” This is when Friedmann—dressed in a fluid-resistant gown and an N95 mask procured through county funding to add to his office’s limited supply of personal protective equipment (PPE)—met patients at their cars to take vital signs and perform COVID-19 tests.

“It was like a car hop,” says Friedmann, who began his career in medicine as a combat medic with the U.S. Army’s Green Berets in Vietnam. “I’d have on my space suit and run out there and swab them.”

Friedmann also received additional funding through HHS’ COVID-19 Rural Health Testing Program to retrofit the part of his clinic that wasn’t in use so it could become an infectious disease ward for patients who had symptoms of COVID-19. Here, he put in new flooring, set up a ventilation system that was separate from the other side of the clinic, and created a new entrance for patients. Since March 2020, he has performed 400 tests for COVID-19, diagnosed 57 patients with the virus that causes COVID-19, and administered 800 COVID-19 vaccines.

“If it weren’t for a PA here [in Redfield], they wouldn’t have any access to care locally,” says Friedmann, who has been affiliated with the clinic since 1985.

According to the National Rural Health Association (NRHA), 15% of PAs in clinical practice work in rural communities. They experienced both positive and negative impacts from the pandemic, ranging from sought-after policy wins that improve the ability to improve access to care, to the many barriers to delivering care experienced by so many healthcare providers.

On the one hand, several pieces of legislation have been fast tracked because of COVID-19 that will benefit PAs in rural health well into the future, and that has been one bright spot in a very difficult time. This legislation directly addresses some of the ways to modernize laws to improve rural access listed on the NRHA’s Policy Brief.

But PAs in rural communities also faced many barriers during COVID-19, including space shortages, vaccine hesitancy, and the need to protect themselves so their communities would continue to have access to care.

Perhaps the biggest barrier has been the general thinking that COVID-19 wouldn’t become widespread in rural areas—a theory that left these communities overlooked early on, says William John Gill, PA-C, who practices at AdventHealth Family Medicine in Wauchula, Florida, a primarily agricultural community of about 5,000 people.

“When all of this hit, the focus was certainly on urban areas and the rural areas were sort of put to the side, just in terms of having testing available and having resources and vaccines,” adds Gill, a former military medic who became one of the first PAs to be licensed in Florida in 1974. “I don’t want to criticize anyone. [Everyone] was trying to make it up as we went along and do the best we can. [But] I think now the effort really has gotten underway and is much, much better.”

Treating COVID-19 in a Critical Access Hospital

For the last 25 years, Mark Zellmer, PA-C, DFAAPA, has practiced at Gundersen Tri-County Hospital and Clinics in Whitehall, Wisconsin, a town of nearly 1,600 people whose economy centers on manufacturing and agriculture. This critical access hospital is licensed for 25 beds, but generally cares for a maximum of 12 patients at one time.

The fall of 2020 was an exception. Then, the hospital saw its biggest spike in COVID-19 cases and providers were caring for up to 18 patients at one time. “In order to manage patient volume, we moved all of our non-COVID-19 patients to another section of the hospital,” Zellmer says.

The rooms in this section were originally built as hospital rooms but had long been used by Gundersen Health System specialists, who traveled the 50 miles from the health system’s headquarters in La Crosse to care for patients. Specialty outreach was paused for most of 2020, so the rooms were available. The hospital had also closed its surgical and procedural suite and one of its outpatient clinics, so the nurses and other staff who normally worked in those areas, along with several volunteer physicians, were reassigned to care for patients who weren’t affected by COVID-19 in this secondary unit.

On the other side of the hospital, Zellmer and his colleagues cared for a maximum of about 10 patients who had been diagnosed with COVID-19 at one time. Zellmer often had a close connection to his patients, making it challenging and emotionally difficult when some of them had particularly severe cases of COVID-19.

“One of the joys of working in a rural community is that you get to know families,” he says. “But it was typical that patients we were caring for were family or friends of somebody we knew or that worked at the hospital. And we had some pretty sick COVID-19 patients, some of whom didn’t make it. To take care of sick COVID-19 patients in that context made it doubly hard.”

The perception of COVID-19 in Whitehall and surrounding communities was also challenging. Not everyone agreed with the hospital’s policy requiring patients, visitors, and staff to wear masks, or that masking was an effective way to control COVID-19 in general. “We’re struggling to find the adequate PPE and trying to keep ourselves safe, and you’d go down to some of the local businesses and there’s only one person in the grocery store wearing a mask,” Zellmer says.

But there were also many instances of people going above and beyond for others. At Gundersen Tri-County, where the cafeteria was turned into a vaccine clinic for three months, up to 250 patients a day received vaccinations because the hospital’s nurses worked overtime to administer them. “They basically gave up all of their days off to come in and run the vaccine clinic,” Zellmer says. “It was pretty amazing how committed [they] were to make it work and [run] smoothly.”

Switching to Telemedicine to Protect Patients and Providers

In Nebraska, Roger Wells, PA-C, spends most of his time practicing at the Family Medicine Specialists Clinic, part of the Lexington Regional Health Center network in Lexington, Nebraska. Lexington’s biggest industry is meatpacking, and 2,000 of the community’s 10,000 people are employed at local plants. They were all essential workers during the pandemic. About 37% of the population is also classified as “foreign born” according to 2019 census data.

When COVID-19 hit the clinic, Wells spent most of his days treating patients through telemedicine. Along with helping the community—particularly those who still had to physically be at work—this also protected providers and staff, which was important as having them unable to come to work because of quarantine would impact patients’ access to care. “We have a very small clinic with a [small] number of providers,” says Wells, who was an athletic trainer for a few years before going to PA school. “We could not allow that to happen.”

But there was a big barrier to providing virtual care. Many patients from some cultures and ethnicities were not comfortable with the process of calling the clinic to set up an appointment, then later receiving a call back from a staff member and an interpreter to confirm a date and time for a virtual call, discuss symptoms, and set up a virtual platform. Then later, when the virtual platform called patients for their appointments, many didn’t recognize the number, feared they were receiving a spam call, and didn’t answer. This combined with a lack of broadband locally meant that Wells and his colleagues had to abandon the virtual platform many times and have phone conversations instead.

“We were not prepared for those challenges but developed a process to expedite the appointment process and improve patient care,” Wells says. “[And] the people did a fine job. They knew how to isolate themselves. Because of the good response within the community, we didn’t have the hospitalization levels that many people would expect.”

Addressing Vaccine Hesitancy

As of August 2021, COVID-19 cases are increasing across the U.S. again, and the state of Florida accounts for 20 percent of all new cases. According to The Hill, Jeffrey Zeints, the White House COVID-19 coordinator, said this trend will likely continue in coming weeks, particularly in communities with lower vaccination rates.

To encourage vaccination in Wauchula, Florida, Gill explains to his patients that the alternative could not only be a COVID-19 diagnosis but also the potentially lingering symptoms known as Long COVID-19. Gill sees several patients with Long COVID-19 who have continuing pulmonary and neurological issues, and their treatment is ongoing. Gill often refers these patients to specialists, then, once they have a treatment regime, follows up with them periodically to make sure they remain stable. If their condition deteriorates, he will refer them back to specialists.

“If you are vaccinated, you are very likely to get through this pandemic, but contracting COVID-19 could lead to long-term effects beyond the pandemic,” says Gill, who was the president of the National Association for Rural Health Clinics for 16 years. “That’s how we try to encourage immunization in patients.”

In Iowa, Friedmann says that his patients mainly have two reasons that make them leery of COVID-19 vaccinations: they think the vaccines haven’t been proven safe because they were developed too quickly or they are going to wait until more time has passed to see if those who received the vaccine have adverse reactions. He addresses these concerns through one-on-one conversations with patients during their regular appointments.

[How to Talk to Your Patients About COVID-19 Vaccination]

Friedmann will bring up the subject, asking if they have been vaccinated and offering to make an appointment for them at the clinic. He explains he has been vaccinated, as have his staff, and that the vaccines are safe, effective, and free. Then he’ll give them time to ask questions and have a conversation about their concerns. “We try to do it in the room where it’s private,” he says. “That works [as a place to begin the conversation] for most people.”

New Legislation Focused on PA Reimbursement and Removing Barriers to Care

Having worked in rural health for 35 years, Friedmann, who also has an undergraduate degree in political science and is a former AAPA President, combines his two areas of expertise as the vice president of AAPA’s Rural Health Caucus. In this role, he advocates for improved laws related to equitable reimbursement and removal of barriers to care in rural areas—changes that could draw more healthcare providers to practice in these communities. “Recently, we’ve been fairly successful,” says Friedmann, adding that this is a direct result of COVID-19. “We got a couple provisions that are very good for rural health.”

As part of the 2020 Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, the Medicare maximum allowable reimbursement rate for independent rural health clinics will steadily increase over the next seven years. The first increase happened in early 2021 with the rate jumping from $87.52 per visit to $100 per visit. That amount will continue to increase through 2028 when it reaches $190 per visit. “That [additional money] is going to enable us to keep going and encourage others to do likewise for other small towns,” Friedmann says.

Additionally, the PA Direct Payment Act, part of the Coronavirus Relief & Omnibus Agreement that was enacted at the end of 2020, allows PAs to receive direct payment through Medicare as of January 1, 2022. This will put PAs on par with physicians, NPs, and other providers who are already eligible to receive direct payment. The change will be particularly helpful for Friedmann’s practice because the current Medicare law says that there needs to be at least one non-PA who partially owns a healthcare corporation/practice in order to receive the Medicare reimbursement for certain services. Friedmann is the sole owner of his clinic, so he can’t get reimbursed for certain lab tests required by Medicare. “That direct payment will get rid of that problem that costs us about $5,000 a year,” he says.

The CARES Act also authorized PAs to certify and recertify patients to receive home healthcare instead of having to wait until physicians can visit clinics to approve certifications. This effectively expands the care available to rural patients.

“The silver lining in the dark cloud of COVID-19 actually has given us the opportunity to improve legislation,” Friedmann says. “That has helped us improve access to care quite a bit.”

Jennifer Walker is a freelance writer in Baltimore, MD. Contact Jennifer at [email protected].

You May Also Like

PAs in Rural Locations Ready to Meet Primary Care Needs

Treating Patients with Long COVID-19: A New Frontier for Providers

2019 PA of the Year ‘Lives to Serve’ New Mexico’s Rural Communities

Volunteering in Imokalee, Florida: Finding My Purpose in Medicine

Thank you for reading AAPA’s News Central

You have 2 articles left this month. Create a free account to read more stories, or become a member for more access to exclusive benefits! Already have an account? Log in.