PAs in Rural Locations Ready to Meet Primary Care Needs

Most Specialize in Family Medicine

June 12, 2018

By AAPA Research Department

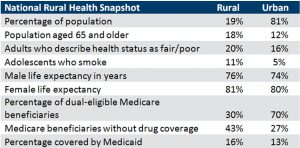

One in five people in the U.S. lived in a rural area in 2016.1 The Rural Health Research Center estimated that following the passage of the Affordable Care Act, the 725,000 new enrollees in rural areas would generate an additional 1.39 million primary care visits.2 Those who live within rural locations are older and live longer, report that they are in worse health, have more adolescents smoking, and are more likely to be on Medicaid and less likely to be dual-eligible Medicare beneficiaries. Those on Medicare lack drug coverage.3

In 2017, one in eight PAs worked in a rural location.

Kushins, Heard, and Weber (2017) suggests that PAs are a solution to the dearth of primary care services in rural areas by having PAs own and operate private care practices in areas that have been traditionally overlooked by healthcare businesses.4 The Bipartisan Policy Center and the Center for Outcomes Research and Education brought together a variety of stakeholders to discuss the state of rural healthcare. One of the recommendations was supporting the primary care physician workforce, including building the PA workforce.5 So what do we know about the PA workforce in rural locations?

About 16% of all clinically practicing PAs were located in a rural county, with 84% in an urban county. The US Census Bureau estimated that in 2016, 19% of the US population was living in a rural location.1

PAs in rural locations work more autonomously.

Half of clinically-practicing PAs in rural locations indicated that their collaborating physician was on site 60% of the time or less and they spent less time consulting with their collaborating physician (half spent less than 5% of their time) compared to PAs in urban locations (75% and 10% respectively). One reason for this may be the high percentage of PAs in rural locations practicing in family medicine and urgent care. Regardless of their settings, 92% of PAs rated their relationship with their collaborating physician either extremely or somewhat positive.

More PAs in rural locations specialize in primary care.

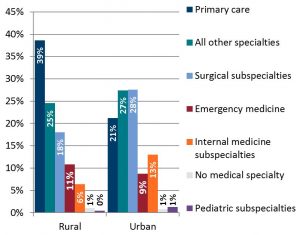

More than one in three (39%) PAs in rural locations were practicing in primary care compared to 21% of those in urban locations. This supports researchers who say that PAs can be positioned to meet the rapidly growing primary care needs in rural locations.2,4,5 When looking at primary care in-depth, PAs practicing in family medicine are driving this pattern. Thirty-three percent of PAs in rural locations identified their primary specialty as family medicine, compared to 14% of those in urban locations. The difference is not as striking for PAs practicing emergency medicine (11% versus 9%) nor urgent care (9% versus 6%) but these differences are still significant.

A greater proportion of PAs in rural locations own their own practices.

In line with the suggestion of PA practice ownership as a model of disruptive innovation put forth by Kushins and colleagues4, a greater proportion of PAs in rural locations own their own practices (2% versus 1%). While these numbers are small right now, it may serve as an indication that growth is possible.

Clinically-practicing PAs in rural locations see more patients.

Clinically-practicing PAs in rural locations see 73 patients each week on average, and half see 68 or more. This is compared to 68 patients each week for those in urban locations with half seeing 60 or more. These numbers are not surprising given the high number of patients seen by PAs in urgent care and emergency medicine, and the fact that there are more PAs in rural locations who work in urgent care and emergency medicine. There was no difference in whether or not they took call.

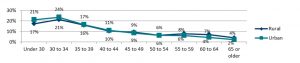

PAs in rural locations are older.

This may indicate a loss of clinically-practicing PAs in rural locations in the next 10 years as they approach retirement age. One in five (19%) clinically-practicing PAs in rural locations are approaching retirement (ages 55 and older) compared to just 13% of those in urban locations.

Most PAs in rural locations work in an outpatient clinic or physician office.

The outpatient clinic or physician office is the most common setting for a PA in a rural location (63%) and they are more likely to be in that setting compared to their urban counterparts (53%). Interestingly, while PAs in rural locations are more likely to practice emergency medicine, they are still less likely to work in a hospital compared to those clinically-practicing PAs in urban locations (26% versus 38%). This is driven by the greater proportion of PAs in urban locations that work in surgical and internal medicine specialties.

Rural PAs are no more burned out than urban.

Despite seeing more patients with less support from their collaborating physician, clinically-practicing PAs in rural locations are no more likely to report being burned out. Across all clinically-practicing PAs, 29% are at risk for burnout, according to their score on the professional fulfillment index.

More Resources

In a recently published policy brief co-authored by National Rural Health Association (NRHA) members, the organization puts forth its views in “Physician Assistants: Modernize Laws to Improve Rural Access.” The brief also outlines recommendations to enable PAs to maximize their contribution in delivering healthcare in rural settings. Notably, these recommendations are fully aligned with AAPA’s policy, Optimal Team Practice.

References

- New census data show differences between urban and rural populations (American Community Survey). News release of the Census Bureau, Suitland, MD, December 8, 2016. (Release no. CB16-210.) Found online https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2016/cb16-210.html. Published December 8, 2016. Accessed June 8, 2018.

- Larson EH, Andrilla CHA, Coultheard C, Spetz J. How Could Nurse Practitioners and Physician Assistants Be Deployed to Provide Rural Primary Care? Rural Health Research Center; 2016. http://depts.washington.edu/fammed/rhrc/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2016/03/RHRC_PB155_Larson.pdf. Accessed June 8, 2018.

- NRHA. About Rural Health Care. https://www.ruralhealthweb.org/about-nrha/about-rural-health-care. Accessed June 8, 2018.

- Kushins ER, Heard H, Weber JM. Disruptive innovation in rural American healthcare: the physician assistant practice. International Journal of Pharmaceutical and Healthcare Marketing. 2017;11(2):165-182. doi:10.1108/ijphm-10-2016-0056.

- Rural Health Care: Lessons Learned. Bipartisan Policy Center; 2018. https://bipartisanpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/BPC-Health-Rural-Health-Care-Summary.pdf. Accessed June 8, 2018.

About the data

The 2018 AAPA Salary Survey was collected between Feb. 2 and March 2, 2018. The survey was sent to the 78,244 PAs (both AAPA members and nonmembers) who had not opted out of communication from AAPA, were based in the U.S., were not identified as retired, and had valid email addresses. A total of 9,140 PAs responded to the survey. The overall margin of error is +/- 1.05% at the 95% confidence level. Response rates and margins of error vary by breakout.

Respondents were asked to provide the county in which their primary employer was based. AAPA used the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Economic Research Service (ERS) Rural-Urban Continuum Codes for determining the rural/urban location. For more information, please see: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes/.

Author is Noël Smith, MA, AAPA’s senior director of research. Contact her at [email protected].

Thank you for reading AAPA’s News Central

You have 2 articles left this month. Create a free account to read more stories, or become a member for more access to exclusive benefits! Already have an account? Log in.