Suicide Prevention Training a Critical Initiative for PAs Lisa Riley and Ali Walker

“This is something we as PAs are uniquely positioned to address.”

September 8, 2023

By Dave Andrews

Nearly 50,000 Americans die by suicide each year. According to the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP), an estimated one-third of those individuals visited a primary care provider in the month before their death.

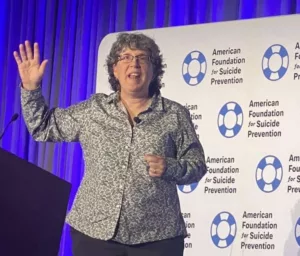

Knowing how to give patients with suicidal thoughts the support they need is becoming increasingly important for all providers—not just mental health professionals. For that reason, Lisa Riley, PA-C, MHP, and Ali Walker, PA-C, RRT, have been working for the past two years with AFSP to develop a formal education module for PAs on suicide prevention.

“Even with all of the knowledge we have and training we receive as providers, most of us do not get sufficient education around suicide,” said Walker, a critical care PA at George Washington University Hospital. “The program we developed is designed to help providers understand suicide on a more clinical level, to facilitate more meaningful conversations with their patients, and to have a better grasp of the available resources and treatment options.”

Riley and Walker are personally committed to raising mental health awareness, as both have lost close friends and colleagues to suicide. And through their clinical experiences, both are keenly aware of the growing need for suicide prevention education for providers—especially for PAs, who serve in diverse roles and provide care to a variety of patient populations.

Becoming Comfortable

A large component of their education program focuses on strategies to help providers normalize difficult conversations about suicide. The initial hurdle for many providers is to overcome any averseness to asking the patient deeply personal questions about their mental health.

Even as a fervent advocate for mental health, Riley, a full-time assistant professor in the PA program at the Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences, admits that early in her career, she was hesitant around patients who showed signs of severe depression.

“Of all the things I’ve asked my patients throughout my career, the hardest for me was asking, ‘Are you thinking about suicide?’” said Riley, who worked as an orthopaedic surgery PA for 30 years before becoming an educator in 2018. “Back then, I was afraid of what their answer would be. And in the back of my mind was the myth that by asking someone that question, it puts the idea in their head. But we know that’s simply not the case.”

Riley, who serves as a national board member of AFSP, says that practicing through role play is one of the best methods for providers to normalize those conversations. It also helps providers realize they can approach mental health similar to how they would treat a patient’s physical health.

“Even though I wasn’t a psych PA, I still had multiple scenarios with patients where I needed to help them through a mental health crisis,” Riley said. “Just like with any other treatment, I assured them I was going to be with them throughout the process, we’d go over options and resources available to them, and then we’d create a plan.”

Changing Perspectives

For the past five years, Walker has spent much of her non-clinical time volunteering through her local Washington, D.C. chapter of AFSP. While serving as an AFSP board member and eventually as its chairperson, Walker helped coordinate and participated in a variety of events to promote suicide prevention.

Walker is now focused on helping healthcare systems integrate mental health and suicide prevention programs. She also helps area hospitals coordinate free education sessions for the public to raise awareness and reduce stigma surrounding suicide. Within a relatively short period of time, she says she has seen a noticeable shift in mental health awareness and less apprehension regarding the topic of suicide.

After losing a close friend to suicide in 2010, Walker recalls feeling uneasy when she spoke about it to her friends and family. “I could tell they would get uncomfortable and wouldn’t know what to say,” she said. “And it was painful for me too; I was going through my own grief, and I didn’t really have anyone to talk to about it. It was an awful feeling.”

Since that time, Walker has noted how people—both healthcare providers and the general public—are much more accepting of and sympathetic toward individuals who are struggling with their mental health.

“I think a big reason why is that people are increasingly realizing that managing mental health is something we all must do,” Walker said. “And whether we need a clinical diagnosis or not, we all have our ups and downs and, we’re getting better at recognizing when something isn’t right.”

Recognizing the Warning Signs

Realizing someone may be dealing with severe depression and thoughts of suicide is not always easy. Riley advises providers, friends, and family members of those who may be struggling to look for key changes in behavior. Those changes often involve the person not showing up to work, avoiding social activities, using drugs, or consuming more alcohol.

“We typically think of a person who is suicidal as someone who is very withdrawn and sad looking,” Riley said. “While that certainly can be the case, some people don’t exhibit those stereotypical warning signs. So, it’s more about how their behavior has changed. Are they more restless? Are they drinking more? Abusing substances?”

Other red flags can be found indirectly in the language they use, Riley says. People with suicidal thoughts will often speak about their own death or how they are a burden on others. But those comments might be misinterpreted as merely jokes or self-deprecation when they should be cause for concern.

“One of the biggest red flags I’ve noticed is when people say they feel a sense of burdensomeness,” Riley noted. “We see that a lot in healthcare, especially among patients who have chronic pain and illnesses, which can often lead to those feelings of depression.”

Getting Involved

Riley and Walker are eager to present an overview of their education module later this year at the PAEA Education Forum. And in addition to advocating for more PA training on suicide prevention, they continue to encourage their provider colleagues to become more familiar with existing resources and to get involved with their local AFSP chapters.

“This is something we as PAs are uniquely positioned to address,” Walker said. “The more comfortable we are talking about suicide, the more comfortable and willing our patients will be talking to us about it. And all it takes is one conversation to make a meaningful impact—for someone to feel supported and inspired to get the help they need.”

If you or someone you know might be at risk of suicide, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255, or visit suicidepreventionlifeline.org.

Dave Andrews is a freelance writer and public relations professional based in Northern Virginia. Contact him at [email protected].

You May Also Like

What Every PA Should Know About Mental Illness and Suicidal Ideation

PAs: It’s Time to Talk About Suicide

Mental Health is Part of Everyone’s Health: Psychiatry PA Jessica Tabb Wants to Change the Narrative Around Mental Health Care

Thank you for reading AAPA’s News Central

You have 2 articles left this month. Create a free account to read more stories, or become a member for more access to exclusive benefits! Already have an account? Log in.