From Addiction and Tragedy, PA Josh Thornhill Treats Body and Soul

Former Detroit Lion Cares for Community Members Through Faith-Based Recovery Program

December 22, 2022

By Hillel Kuttler

Josh Thornhill sees patients every day as a PA at NorthCrest Orthopaedics & Sports Medicine in Springfield, Tennessee. But on Tuesday evenings, Thornhill, 42, takes care of other people: approximately 100 men and women who come to an area church to confront their addictions – primarily to medications, alcohol, illicit drugs, food, and pornography – and to deal with their anger, depression, and anxiety.

Thornhill isn’t a cleric or a therapist. What he brings to the volunteer position is life experience as a high achiever who’s endured formidable challenges, the greatest being the death of his young son.

Facing Addiction and Loss

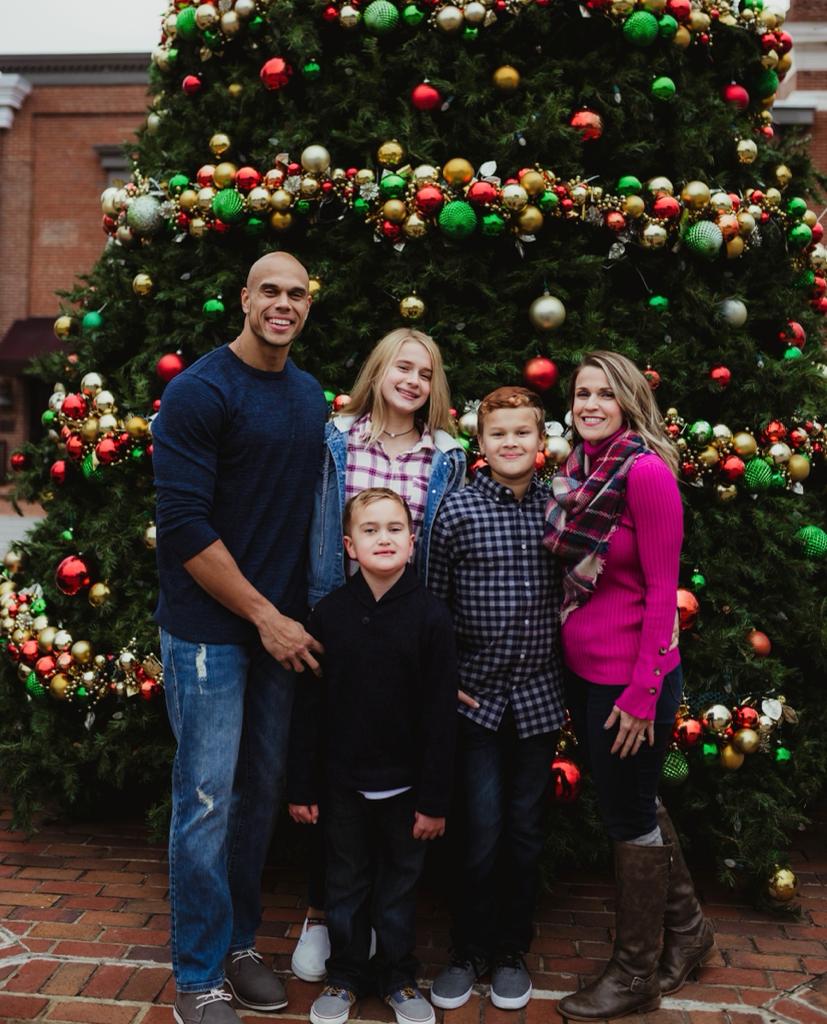

Thornhill experienced chronic back pain while playing football for Michigan State University and the NFL’s Detroit Lions. He underwent knee and shoulder surgeries. He broke a foot. In 2011, he suffered a herniated disk and shooting pain in both legs while jumping out of bed, mistakenly thinking that an intruder had entered the home he shared with his wife Katie and their children Hannah, Isaac, and Marcus.

Several months on Vicodin should have helped. Thornhill took it for five years. He found providers to prescribe the opioid painkiller and came up with “other ways to get it,” he said, not wishing to elaborate.

“It’s easy, with an athletic career, to say you’re in pain. I liked the way it felt,” Thornhill explains. “Parenting young kids [subsequently] wasn’t stressful. It helped with the job. It gave you an overall sense of feeling good.” He moved to abusing alcohol – whatever was available. It wasn’t the taste that he craved. “I drank it so I couldn’t feel,” he said.

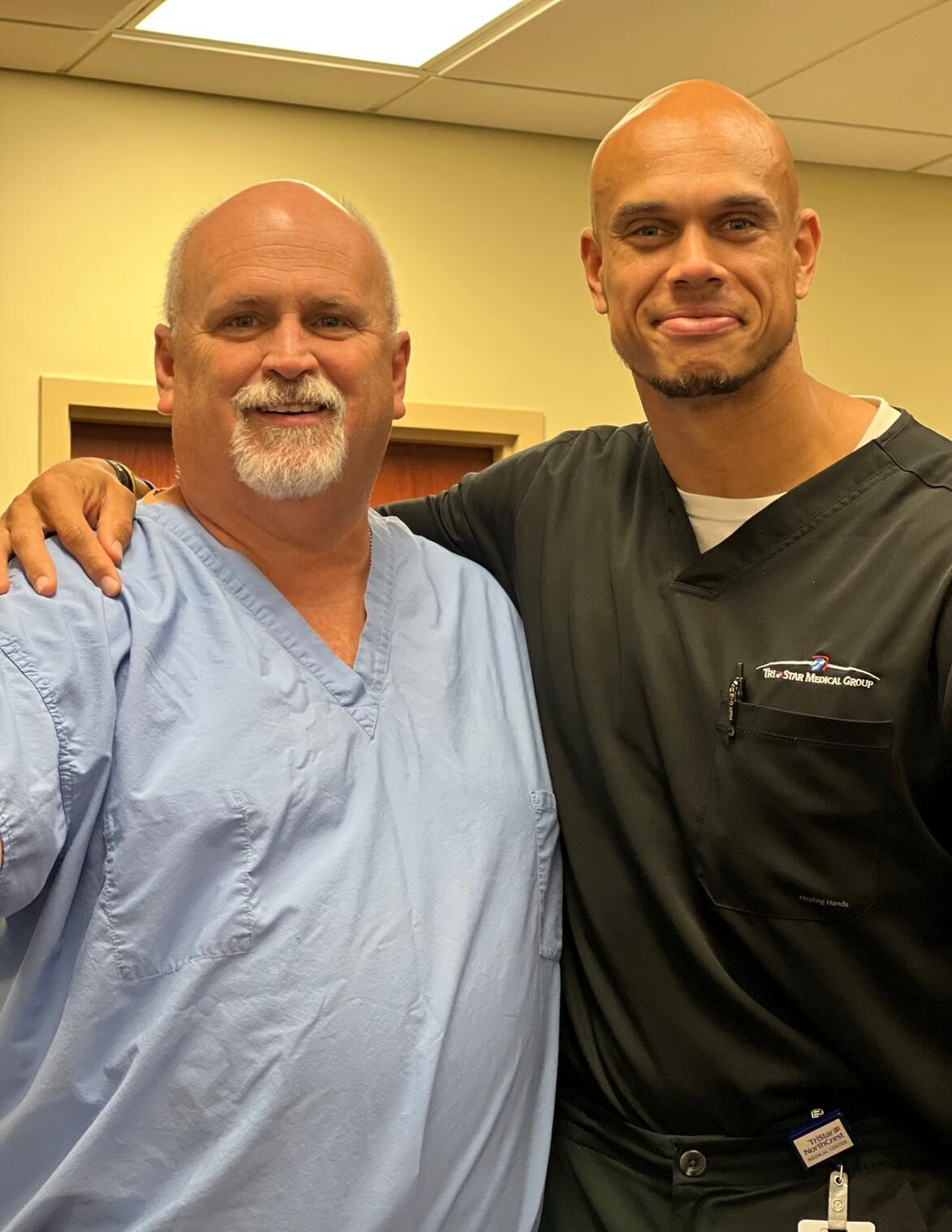

People at work noticed changes. His boss, William Beauchamp, MD, said that Thornhill’s “spark” was missing, that he seemed “more tired than usual, more distant.”

“This is a guy whose body was fine-tuned, physically fit, who worked out like a demon, but you could tell his energy was gone. It smelled bad to me,” Beauchamp says.

Thornhill didn’t know it, but his job was at risk. Katie considered leaving him. In late 2016, Beauchamp met with them both.

“I told him I needed him to go home, pack his stuff, and go to rehab in the morning,” Beauchamp said of the meeting. Thornhill nodded glumly. He had patients, so he preferred waiting until the following Monday to enter a treatment facility.

“No,” Beauchamp said. “Now.”

The next morning, Katie drove her husband 200 miles south to the facility in Warrior, Alabama, where he remained for three months.

“There was lots of pain embedded down deep,” Thornhill says. In therapy, Thornhill traced the hurt to unresolved grief over the sudden passing of his father, Charles, nicknamed “Mad Dog,” who preceded Josh and his younger brother Kaleb as a star linebacker at Michigan State. Marital problems played a role, too. Being in rehab “saved my marriage, my job, my life,” he says.

Back home, Thornhill attended mandatory meetings of a recovery group – three groups, in fact. He gravitated to one in particular: a national organization called Celebrate Recovery, because it is religion-based. He and Katie, members of a nondenominational church, started a chapter in spring 2018.

Thornhill became sober just in time, it turned out, to tackle a parent’s ultimate nightmare. That June, six-year-old Marcus – the most energetic of the three children, a boy for whom happiness meant bouncing on trampolines – was diagnosed with brain cancer. He died two years later.

Finding the Silver Lining

After beginning his PA career in emergency medicine in his native Michigan, Thornhill moved in 2012 to Tennessee, where Katie’s sister lived. In 2015, he ran into Beauchamp. They had crossed paths years earlier, up north. Beauchamp had watched Thornhill play at Lansing’s Eastern High School and at Michigan State during Beauchamp’s orthopaedics residency.

At their chance meeting, Beauchamp suggested that Thornhill switch to orthopaedics and recruited him. Seeking a more favorable schedule for his home life, Thornhill accepted the job offer.

When Beauchamp ordered Thornhill into rehab in 2016, he knew the challenges all too well. Enduring a divorce six years earlier, Beauchamp drank heavily and himself entered treatment. “Josh and I have an inside relationship, having gone through that,” Beauchamp says.

Like a contrite player accepting a referee’s ejection, Thornhill considered Beauchamp’s decision correct. He now points to a silver lining.

“If it hadn’t been for what I learned in recovery, there’s no way I could’ve walked through the battle with Marcus. … Had I been dealing with addiction on top of that, I wouldn’t have been there for Marcus,” he says.

“I got clean before Marcus’s diagnosis. That was huge, because had [the] diagnosis been before that, it would’ve been more tragic than it already was. I would’ve been trying to numb my feelings, which would’ve been devastating. I was able to stay sober through that.”

Running a Volunteer Ministry

Two ways he continues moving forward are through work and the ministry. Thornhill says he finds gratification in helping patients – about 40 percent of them are recreational and competitive athletes – to recover from injuries and return to action. And running the recovery program after having gone through it, he said, “gives me a level of empathy for everybody.”

Each Tuesday meeting begins with socializing and a buffet dinner. A speaker presents a theme helpful in recovery – on a mid-August night, it was forgiveness – followed by a prayer. Afterward, women and men head separately into sessions on, as Thornhill calls them, the “hurt, habit, or hang-up” with which they’re grappling.

For Thornhill, teamwork applies there just as in the medical and sports settings to which he’s accustomed. He relies on other volunteers to undertake tasks in their areas of expertise, such as budgeting, preparing schedules, and printing materials.

Volunteering in the ministry, Thornhill says, has exposed him to “how much need there is, how many hurting people there are, how important the work we do is.” It’s given him purpose in his recovery from addiction and in his emotional healing.

“I’m finding help through this ministry with grief,” Thornhill says. “It’s helping me more than I’m helping other people. It reminds my heart to remain on the path I’m currently on.”

Kaleb Thornhill credits his older brother for persevering.

“The mental, psychological, spiritual, physical, and psychosocial [challenges] in what he has endured – he’s one of the strongest, most resilient people I’ve met. To take that many punches and keep moving forward – I don’t know how he did what he did,” said Kaleb, a Florida-based consultant for professional athletes.

“The ministry, in my opinion, saved his life and his marriage,” says Shane Davis, who helped Thornhill establish the ministry and is now a close friend. “A lot of people going through what he’s gone through would be utterly broken. I’ve seen him struggle with grief and emotions, but he’s come out a better man than before his son’s illness – a much more present husband and father.”

Thornhill is “Back in the Game”

To eavesdrop on the Thornhills’ Facebook posts is to experience an emotional whirlpool. We enter Katie’s dread – with machines beeping and Marcus struggling for air, his lips and fingers turning blue – that her son would die that morning in May 2020, Mother’s Day. And her calm, perhaps shell-shocked, entry a month later, after Marcus died at home: “My heart aches that it’s Father’s Day and Josh has to spend it as the first full day without his youngest son on this Earth.”

We read his writing about a new “life in grey” of a family vacation with one absence, her quotations from Scripture, and their loving birthday wishes to each other.

We gaze at pictures of a handsome family of five, and then of four. We stare into the eyes of a smiling, healthy-looking boy as he flexed a muscle; he loved wrestling. We see him on a hospital bed at home, tubes dangling, sleeping. We freeze upon a black-and-white image of father, mother, sister, and brother clustered at the head of Marcus’s open casket.

Thornhill says he’s emerged a better person.

“I don’t believe what we went through was pointless,” he says.

Thornhill says he’s gained a new “level of empathy” for people and is really present for his patients, especially those enduring hard times – including addictions. He seems disappointed when calling out some medical providers as “judgmental” about patients they consider “pill heads” for craving painkillers.

“Well, they don’t want to be there,” he says of the patients. “I certainly can understand other people’s pain… At least they know they’ll come across somebody who won’t judge them or label them.”

Helping athletes, parents, coaches, and trainers deal with players’ injuries also brings fulfillment, Thornhill says. It’s what he calls “the sports medicine piece” of his work as a PA that comes from having been an elite sportsman.

“It’s trying to problem-solve on the unique issues athletes face,” he says. “It’s finding unique ways to get athletes back in the game.”

Thornhill endured severe wounds. He is back in the game.

Writer-editor Hillel Kuttler can be reached at [email protected].

You May Also Like

Five Things You Should Know From an Addiction Medicine PA

PA Students: Educate Yourself on Preventing Prescription Opioid Misuse

Ortho PA Turns Soccer Passion into Profession

Olympic Skiers and Snowboarders Benefit from PA Care

Thank you for reading AAPA’s News Central

You have 2 articles left this month. Create a free account to read more stories, or become a member for more access to exclusive benefits! Already have an account? Log in.