How to Talk With Patients About Intimate Partner Violence

Providers Can Offer Patient Education

October 24, 2019

By AAPA Research Department and Katherine M. Thompson, MCHS, PA-C, FE

A recent AAPA survey reveals that just 30% of all clinically practicing PAs regularly ask their patients about domestic violence. It rises to 46% among those in emergency medicine, urgent care, and primary care, but is still less than half. Furthermore, 51% of PAs indicate that they have never had training in the treatment/management of domestic violence survivors; of those PAs who have had training, only 60% feel prepared to treat survivors.

About intimate partner violence

Intimate partner violence (IPV), a term which is frequently used interchangeably with domestic violence, is abuse within the context of relationship, where one partner asserts power and control over the other. This may include physical, sexual, psychological, or economic coercion and/or abuse.1 Domestic violence can be any of these subtypes alone, in combination with others, or could change over time. (i.e., someone could experience emotional abuse alone, emotional abuse + physical abuse, or first emotional abuse that escalates to physical abuse). IPV can occur in any relationship dynamic and does not require sexual intimacy.2 Risk factors include individual factors, relationship factors, and societal factors; underlining the idea that no one is immune to IPV.2

Intimate partner violence is a public and mental health crisis that is significantly impacting the healthcare system. PAs are on the frontlines of medicine and whether they know or acknowledge it, they are seeing these patients and interacting with them in their daily practice.

How might this happen? Imagine a person is being abused, knows that it is wrong, makes some sort of attempt at seeking help such as coming to the emergency department (or urgent care, orthopaedic clinic, community health center, or many others). Your patient fails to disclose the abuse because of shame, fear, and a variety of other well-documented reasons. Thus, you are seeing a patient and interacting with them within the healthcare system but not for the reasons they actually need help for, which is the IPV. If the IPV can end, treatment for the trauma may start, and both mental and physical healing may begin.

How common is intimate partner violence?

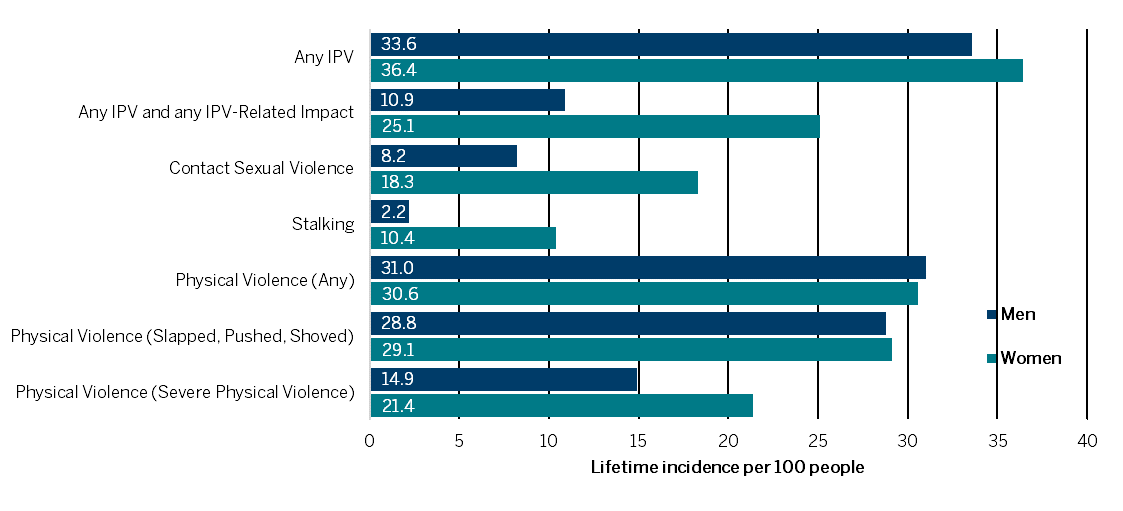

Accurate information on the incidence of IPV is nearly impossible to find, as the crime is by far underreported by the survivors to authorities. The US Department of Justice estimates that the rate of IPV declined from 15.5 to 5.4 per 1,000 women between 1995 and 2015 and from 2.8 to 0.5 per 1,000 men. The CDC reports much higher rates, which highlights the difficulty in estimating its scope. According to the CDC, one in three women (36.4%) and men (33.6%) experienced IPV by an intimate partner in their lifetime (Figure 1). When looking at the estimated incidence of IPV in the past 12 months, the rate is 5.5% of women (or 6.6 million) and 5.2% for men (or 5.8 million).3 Women and men are experiencing IPV at similar rates; there are large disparities, however, in the specific types and in the outcomes (Figure 1). During just one day, September 13, 2018, more than 75,000 survivors of domestic violence received services.4

Figure 1. Lifetime Rate of Intimate Partner Violence by Gender, 20153

How does IPV impact the health of patients?

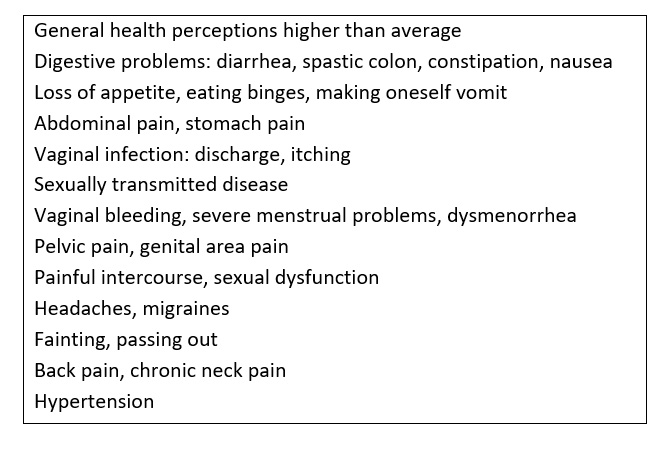

IPV is known to have long-term consequences, both in physical and mental health. These can manifest in myriad ways, including (but not limited to): poor health status, poor health self-perception, poor quality of life, higher incidence of chronic pain syndromes, higher incidence of alcohol/drug dependence, and higher use of healthcare resources.5-7 In addition, IPV is one of the most common causes of injury among women.8 Unfortunately, most women who have experienced IPV report that they have been injured as a result of IPV, but less than half sought treatment for their injuries.9

Figure 2 Significant Physical Symptoms in US Women Who Have Experienced IPV 10

What interventions within healthcare work?

As part of the CDC’s technical support for preventing IPV, they recommend that healthcare providers engage in patient-centered treatment for survivors of IPV.11 The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends screening women of childbearing age for IPV. Healthcare providers could go one step further and screen all patients, regardless of age and gender, for the presence or history of IPV. PAs should keep in mind that most survivors will not disclose their experiences with violence; instead providers may focus on offering patient education on what healthy relationships look like, how to identify signs of abuse, and provide available resources if the patient is experiencing IPV.12

What does work? Brief, women-focused interventions delivered mostly in the primary care office by non-physician healthcare workers were successful at reducing IPV, improving physical and emotional health, increasing safety-promoting behaviors, and positively affecting the use of IPV and community-based resources.13 Violent relationships are dynamic and changeable, and the survivor’s perception of and involvement in the relationship can change at any time. Thus, screenings more than rote annual screenings would be the most powerful tool to provide the greatest global comprehension and intervention.

What can PAs do?

PAs, as healthcare providers, should seek further education opportunities related to IPV. It is also important for PA programs to expand curriculum on this topic, empowering the PA workforce to provide better service for survivors, and to foster a healthcare workforce and culture that does not support intimate partner violence. All PAs can have a role, whether they work in bone marrow transplant or primary care, in addressing and treating IPV.

References

- Office for Victims of Crime, US Department of Justice. Intimate Partner Violence. https://ovc.ncjrs.gov/ncvrw2018/info_flyers/fact_sheets/2018NCVRW_IPV_508_QC.pdf. Accessed September 25, 2019.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Intimate Partner Violence. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/index.html. Accessed September 25, 2019.

- Smith SG, Zhang X, Basile KC, Merrick MT, Wang J, Kresnow M, Chen J. (2018). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2015 Data Brief – Updated Release. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- National Network to End Domestic Violence. 13th annual domestic violence counts national summary. National Network to End Domestic Violence web site. https://nnedv.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Library_Census_2018_National_Summary-1-1.pdf. Accessed September 25, 2019.

- McCauley J, Kern DE, Kolodner K, et al. The “battering syndrome”: prevalence and clinical characteristics of domestic violence in primary care internal medicine practices. Ann Intern Med 1995; 123: 737–46.

- Tollestrup K, Sklar D, Frost FJ, et al. Health indicators and intimate partner violence among women who are members of a managed care organization. Prev Med 1999; 29: 431–40.

- Wisner CL, Gilmer TP, Saltzman LE, Zink TM. Intimate partner violence against women: do victims cost health plans more? J Fam Pract 1999; 48: 439–43.

- Rand MR. Violence-related injuries treated in hospital emergency departments. Bureau of Justice Statistics special report. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, 1997.

- Bachman R, Saltzman LE. Violence against women: estimates from the redesigned survey. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, National Institute of Justice, 1995.

- Campbell JC. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet. 2002; 359: 1331-36. 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08336-8.

- https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/ipv-technicalpackages.pdf

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (2014, December). Final recommendation statement: intimate partner violence and abuse of elderly and vulnerable adults: screening. Published October 23, 2018. from https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Announcements/News/Item/final-recommendation-statement-screening-for-intimate-partner-violence-and-elder-abuse. Accessed September 25, 2019.

- Bair-Merritt MH, Lewis-O’Connor A, Goel S, Amato P, Ismailji T, Jelley M, Lenahan P, Cronholm P. (2014). Primary care–based interventions for intimate partner violence: a systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 46(2), 188-194.

About the data

Data on training on training to treat and manage patients who are domestic violence survivors are derived from a study conducted in 2019 in collaboration with Katherine M. Thompson, MCHS, PA-C, FE of TKTK.

Authors are Noël Smith, AAPA senior director of PA and Industry Research and Analysis, and Katherine (Katie) M. Thompson, MCHS, PA-C, FE. Contact Noël at [email protected] and Katie at [email protected].

More Resources

IPV Educators

Read More

Providing Strength in the Wake of Trauma

Thank you for reading AAPA’s News Central

You have 2 articles left this month. Create a free account to read more stories, or become a member for more access to exclusive benefits! Already have an account? Log in.