Human Trafficking: Become Informed and Be Attentive

PA Offers Tips and Tools for Diagnosing and Counseling Victims

May 30, 2019

Editor’s Note: In May 2019, AAPA’s House of Delegates adopted the following policy: “HX-4400.1.5 AAPA recognizes that abuse and violence are a public health epidemic in the United States. AAPA supports medical care of individuals who have encountered violence including, but not limited to, abuse, neglect and human trafficking and emphasizes linkages with community-based programs and referral agreements whenever possible. PAs should be aware of organizational and state requirements regarding the examination, documentation, and reporting of suspected or reported intentional injury, neglect or abuse. If necessary, PAs are to provide timely referrals to institutions that can perform these services.”

A position paper, adopted in 2019, can be found on page 317 of AAPA’s Policy Manual.

By Leah Bayliss, PA-C

What if we are missing them? What if we could do better? What if, while we are treating patients for their assault, rape, occupational injury, overdose, pregnancy, miscarriage, malnutrition, dental concerns, or sexually transmitted infections, we are still not truly seeing them?

As healthcare providers, we may be the only touchpoint for a trafficking victim. This gives us an opportunity to recognize their situation and a chance to change their lives, not just treat the physical manifestation of their nightmare.

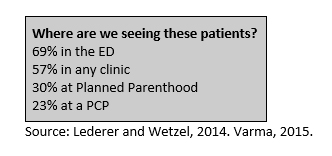

Globally there are an estimated 40.3 million victims of human trafficking. This industry generates a staggering $150 billion worldwide13. Although we have no official U.S. trafficking victim estimate, it may be in the hundreds of thousands13. Healthcare providers may be the only professionals that victims interact with while still in captivity7. Studies reveal that up to 88% of trafficked victims were treated by a healthcare provider while they were being trafficked11. Of those, 97% report they were not offered assistance out of the situation or identified as a victim of trafficking6.

These statistics alarm me. I have been a PA for 12 years, mostly in Emergency Medicine. I have had patient presentations or encounters that seemed as if something was not quite right but honestly, for the first eight years of my practice, not once did I consider human trafficking in my differential. It is hard to spot a diagnosis if you are unaware of it. Looking back, I am sure I missed victims. However, with the guidance of several anti-human trafficking resources and hospital administration support, I am currently leading a Human Trafficking Response Program initiative where I work to increase staff awareness of the prevalence of human trafficking and to develop hospital-wide policy to provide guidance and support to our staff. Staff trained so far include our Emergency Department providers, Nurses, Technicians, Family Birthing Center, Janitorial services, Patient Access, Security, Administration, Patient Relations (Volunteers), Case Managers, Social Workers, and scribes.

Detecting, diagnosing and treating human trafficking victims presents a unique challenge and can be complicated by provider and victim barriers. While research demonstrates that healthcare providers have a lack of Human Trafficking (HT) training to assist in identifying this population9, it can no longer be considered an optional provider competency. Additionally, studies have shown victims to routinely not disclose their victimization for several reasons including, but not limited to, fear of retaliation or deportation, shame, and even healthcare provider distrust 2,4.

PAs have a unique opportunity to be an effective agent of change. Given our role in the clinical setting and the healthcare team, we can increase our personal knowledge of human trafficking and help guide a discussion on staff training for our coworkers and colleagues to recognize human trafficking.

PAs have a unique opportunity to be an effective agent of change. Given our role in the clinical setting and the healthcare team, we can increase our personal knowledge of human trafficking and help guide a discussion on staff training for our coworkers and colleagues to recognize human trafficking.

Included in this article is the definition of human trafficking, history and examination red flags, tips on how to use a trauma-informed approach to patient care, helpful questions that may guide your discussion, recommended next steps following a patient disclosure of trafficking, and additional provider educational resources.

What is human trafficking?

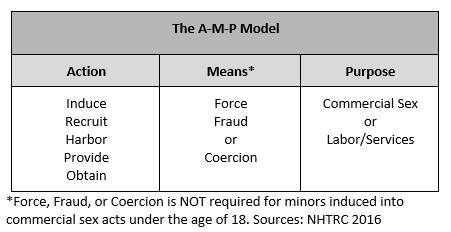

Human trafficking involves the use of force, fraud, or coercion to obtain some type of labor or commercial sex act15. The AMP Model is designed to assist with screening for human trafficking concerns and further define the three necessary aspects of trafficking including Action (what the trafficker does), Means (how the trafficker does it), and Purpose (for exploitation)8.

What does trafficking look like?

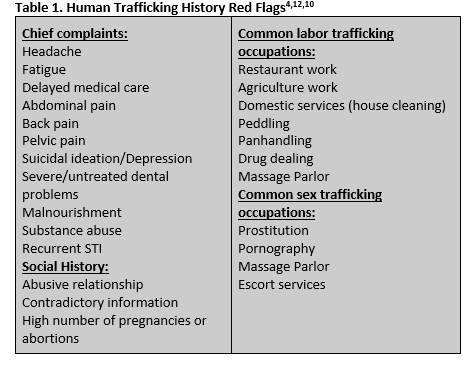

Although labor and sex trafficking affect people of all ages, races, socio-economic status, nationality, and sexual orientation, several vulnerable populations may be at higher risk. These can include children, youth, commercial sex workers, undocumented immigrants, homeless, those with addiction and substance abuse history, mental or behavioral health history, lack of social or family support, young mothers, and patients with learning disabilities. Specifically, for the pediatric population, additional red flags include a history of abuse or neglect, poverty, mental illness, a history of running away, exposure to bullying, lack of supervision, foster children, LGBTQ, and friends and family in the commercial sex industry10,12.

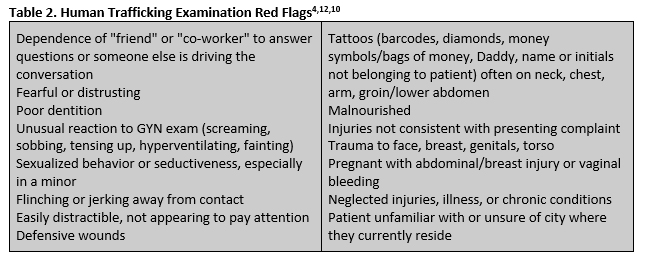

Human trafficking does not have a straight-forward consistent clinical presentation. However, there are several common history and examination red flags that should alert you to investigate further (Table 1 and 2).

How to approach and interact with a suspected victim

Using a patient-centered, trauma-informed approach during your patient encounter can aid in preventing re-traumatization. Providers should be cognizant that all patients may have had traumatic experiences which may dictate how they respond to and interact with health care providers. Stories may change during the encounter, which is not always intentional and can be a symptom of trauma exposure. This can be influenced by patient guilt, fear, shame, and self-protection.

Disclosure is not the goal of the first encounter

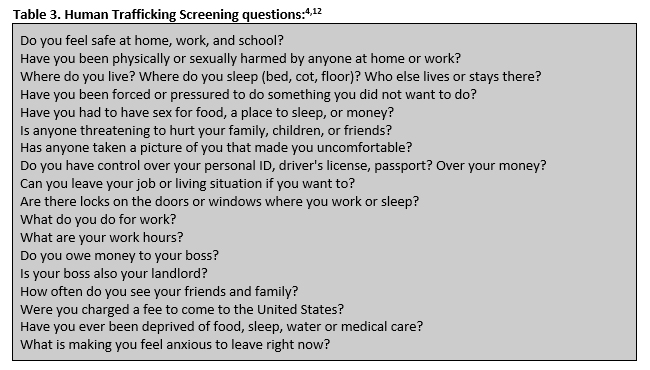

Instead, our job is to treat, educate and empower the patient. Be non-judgmental, compassionate, and open to unfamiliar narratives. Inform the patients that your office is a safe and confidential place. Table 3 provides several questions that may guide your conversation and allow assessment of trafficking risk.

Patient and provider barriers that may be affecting your encounter are also worth considering. Patient barriers include individuals not recognizing themselves as victims, fear of retaliation, mistrust of providers, guilt, lack of awareness of safe alternatives or legal rights, fear of legal consequences or immigration services, and loyalty to trafficker4. Provider barriers can influence our examination as well. These include lack of education or training on Human Trafficking, proficiency of screening for victims, hesitancy due to lack of awareness or available resources, using an accompanying person for translation, time and resources constraints, and emergently sicker patients 4,9.

If an interpreter is needed, consider using the National Human Trafficking Hotline translation services (1-888-373-7888). They have translation available in over 200 languages, 24-hour coverage, can screen persons by phone for victimization and connect callers to local resources.

What to do next

Once you determine your patient is a victim of human trafficking, your next steps will be to assess safety needs and communicate a message of hope. Inform the patient that they have rights, are not alone and this is not their fault3. If safety is an immediate concern and the patient consents, involve security/law enforcement. The Federation of State Medical Boards has information on mandatory reporting requirements for suspected/confirmed HT cases for each state. Be familiar with your state minor mandatory reporting guidelines as well. The National Human Trafficking Hotline website is also available 24/7 as a provider reference and can direct or assist you with the next steps for your patient. It is important to know that undocumented or nonpermanent residents have protected rights if they are being trafficked. More information is available at the Department of Homeland Security’s Blue Campaign website (T-Visa, U-Visa and Continued Presence (CP) Status)4.

If they decline assistance, trust that the patient knows the situational risks associated with leaving. Assure the patient that they are welcome to return to the clinic at any time and can receive additional resources when they are ready. Any referral information you provide will need to be discreet or verbally communicated since traffickers may review or destroy any written instructions. The National Human Trafficking Hotline is available at 1-888-373-7888 or by texting BEFREE (233733).

More Resources

Health Trafficking

Human Trafficking and the Role of the Health Provider

Dignity Health

Human Trafficking and the Healthcare Industry

References:

- “2016 National Hotline Annual Report.” National Human Trafficking Hotline, 10 Apr. 2018, humantraffickinghotline.org/resources/2016-national-hotline-annual-report.

- Alpert E., Ahn R., Albright E., Purcell G., Burke T., Macias-Konstantopoulos W. (2014). Human trafficking: Guidebook on identification, assessment, and response in the health care setting. Boston, MA: Massachusetts General Hospital.

- “Anti-Trafficking Program.” Safe Horizon, www.safehorizon.org/anti-trafficking-program/.

- Baldwin S. B., Eisenman D. P., Sayles J. N., Ryan G., Chuang K. S. (2011). Identification of human trafficking victims in health care settings. Health and Human Rights: An International Journal, 13(1), E36-E49.

- Catholic Health Initiatives. “Human Trafficking and the Role of the Health Provider.” National, www.catholichealthinitiatives.org/en/our-mission/advocacy/violence-prevention/human-trafficking-and-the-role-of-the-health-provider.html.

- Coalition to Abolish Slavery and Trafficking. (2017). Identification and referral in health care settings. Retrieved from http://http://www.castla.org/assets/files/identification_and_referral_in_health_care_settings_survey_report_vjen.pdf [Context Link]

- Dovydaitis, Tiffany (2010). Human Trafficking: The Role of the Health Care Provider. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2010 Sep-Oct; 55(5): 462-467. DOI: 1016/j.jmwh.2009.12.017.

- “Federal Law.” National Human Trafficking Hotline, 26 Sept. 2016, humantraffickinghotline.org/what-human-trafficking/federal-law.

- Frances H. Recknor, Gretchen Gemeinhardt & Beatrice J. Selwyn (2017): Health-care provider challenges to identification of human trafficking in health-care settings: A qualitative study, Journal of Human Trafficking, DOI: 1080/23322705.2017.1348740.

- Ink, Social. “Because Human Trafficking Is a Public Health Issue.” HEAL Trafficking: Health, Education, Advocacy, Linkage, healtrafficking.org/.

- Lederer, Laura, and Christopher Wetzel. “The Health Consequences of Sex Trafficking.” Annals of Health Law, vol. 23, 2014, pp. 61–91., doi:icmec.org.

- “Taking a Stand Against Human Trafficking.” Tissue Plasminogen Activator | Nevada Hospitals | Dignity Health, www.dignityhealth.org/hello-humankindness/human-trafficking.

- “The Facts.” Polaris, 9 Nov. 2018, polarisproject.org/human-trafficking/facts.

- Varma, Selina, et al. “Characteristics of Child Commercial Sexual Exploitation and Sex Trafficking Victims Presenting for Medical Care in the United States.” Child Abuse & Neglect, vol. 44, 2015, pp. 98–105., doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.04.004.

- “What Is Human Trafficking?” Department of Homeland Security, 17 Oct. 2018, www.dhs.gov/blue-campaign/what-human-trafficking.

Leah Bayliss, PA-C, works in Houston, Texas for TeamHealth in Emergency Medicine. Contact her at L[email protected].

Thank you for reading AAPA’s News Central

You have 2 articles left this month. Create a free account to read more stories, or become a member for more access to exclusive benefits! Already have an account? Log in.