Tattoo Removal: A Different Kind of Medicine

PA Troy Clarke Helps People “Move Forward with Their Lives”

April 12, 2019

By Hillel Kuttler

Numbers. Weapons. The sun. A swastika. Fire. Motorcycles. Sports teams’ logos. Flags. Birds. Animals. Religious symbols. Song lyrics. Names. Area codes. Obscenities.

Those are just some of the tattooed words and images Troy Clarke, PA-C, has removed from the necks, arms, faces – nearly every body part there is – of former gang members, recently released prisoners, and those enlisting in the military. Some women he’s helped were forcibly tattooed to claim possession by boyfriends and human traffickers.

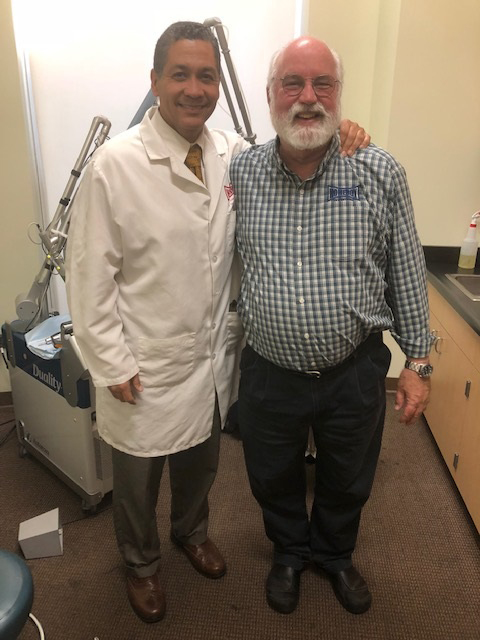

Clarke estimates having removed “multimillion square inches” of tattoos from approximately 80,000 people, including individuals with 1,000 gang affiliations. For more than a decade, Clarke has been employed at Homeboy Industries, a nonprofit organization in Los Angeles’ Chinatown section that also provides anger-management sessions, parenting classes, therapy, and courses to prepare for high-school equivalency exams.

Clarke has removed tattoos from a diverse group of people of many backgrounds: Hispanic, black, white, Armenian, Chinese, Cambodian, and Vietnamese. The organization provides the service for free to help clients turn the page on their past and lead productive, peaceful lives.

[Providing Strength in the Wake of Trauma]

That goal, said Clarke, can’t be attained when the ink screaming from their bodies prevents potential employers and landlords from seeing the person underneath.

“Not being able to move forward with your life is pretty damaging. They’re pretty brave people, the ones who walk through these doors,” he said. “Every time they look in the mirror, they see a tattoo from as far back as age nine.”

Tattoo removal a different kind of medicine

Clarke also has trained more than 100 physicians, PAs, and nurse practitioners who’ve volunteered at the organization to remove tattoos.

The work is a far cry from Clarke’s earlier work as a PA in vascular and general surgery. He’s at Homeboy eight to 10 full days each month, and works elsewhere on a per-diem basis. Clarke lives in Boston with his family. The long-distance commute, he quipped, “allows me to never get over jet lag.”

His removing tattoos is “a different kind of medicine,” with the goal of “having the patient go home healthy [to] live happily,” he said.

“You can actually save a life and improve a life by removing a tattoo. … To have the opportunity to help people move forward with their lives – that’s what medicine is all about. It’s another way to [do] community medicine,” he continued.

“It’s important for me to know that if I’m dedicating my life to medicine, I can be impactful. If a girl has a laceration to her face and is in the ER, I want to help her look forward. That’s what I’m doing here. It’s a good day when someone comes in and says, ‘I have three job opportunities” or ‘I finally got my kids back’ or ‘I started using heroin when I was 11, but I’ve been clean for two years.’ You put all judgment aside and treat that person the best you can.”

Someone Clarke helped is Fabian Debora, a gang member who had abused methamphetamines. From ages 12 to 30, Debora was arrested 35 times and jailed for robbery, assault, car theft, and drug possession. He once ran across a freeway, “hoping a truck would hit me and take me out of my misery,” Debora said.

Acknowledging “the hurt I caused,” Debora said, he went straight in 2006.

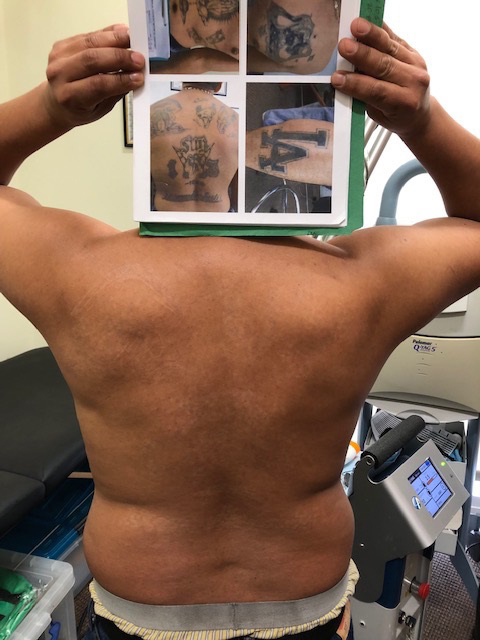

By then, “I looked like a billboard,” with more than 25 tattoos on his back, stomach, legs, face, neck, and arms, he said.

“I looked in the mirror, and the tattoos no longer made sense. They defined who I was as a gang member. The tattoos needed to come off. I felt incarcerated behind the tattoos,” Debora said.

Laser removal can take up to 30 sessions

It’s easier said than done. Removing a single tattoo is painful and can take up to 30 sessions, usually weeks apart, of successively breaking down the ink, explained Homeboy’s medical director, Paula Pearlman, MD.

One physician at Homeboy took 12 sessions with the laser to remove Debora’s first tattoo. It read LA in large, black letters on his neck. Clarke completed the physician’s work in two additional sessions. He then removed the name of Debora’s gang behind his ear.

A tear-drop image was the most challenging because it appeared on Debora’s eyelid. Several physicians declined to work on it, being so close to the eye. Debora approached Clarke.

“Troy said, ‘I think I can work some magic. Why don’t we do it right now?’ He put goggles on my eye and said he’d pull the skin hard. He stretched the skin as far as he could. It was very painful. I felt like the laser was hitting my skull. I’ll take the pain because I needed my freedom,” Debora said.

[PAs’ Efforts to Help Homeless in LA Stymied by Outmoded Regulations]

Clarke goes the extra mile for patients

“I believe that Troy went the extra mile because he knew how much it meant to me. As much as the teardrop was holding me back, Troy allowed for that nightmare to end.”

Clarke removed three others from Debora: Tough Love, from the left arm; Alma Perdida (Spanish for lost soul) from the back of his neck; and his gang’s name, from behind the left ear.

Some of the medical staff will remove only visible tattoos, but people’s emotional pain sometimes carries such weight that exceptions are made. Father Greg Boyle, Homeboy’s founder, spoke of a man with a tattoo on his chest for whom the removal was initially denied.

“No one will see it,” the man was told.

“My son will see it,” he replied.

The tattoo was removed.

Clarke tends to be more flexible than others. He draws the line at removing the name of someone’s ex-girlfriend/-boyfriend, because that would cheapen the mission.

“We can’t have the reputation of removing just any tattoo,” he said.

Honest interactions lead to empowerment

His demeanor is one of Clarke’s greatest assets as a PA, Pearlman said. As a clinician, Clarke doesn’t sugar-coat the physical pain people can expect to endure while their tattoos are removed, she said.

“He’s honest, but in a way that’s empowering,” she said. “While he doesn’t couch the reality, it’s one that can lead to a better future.”

More than that, Clarke’s sharp wardrobe and precise grooming project respect, since clients aren’t used to people in suits treating them well, Pearlman said.

In so doing, Father Boyle said, Clarke creates “exquisite mutuality” with clients.

“He’s allowing himself to be reached by them, and vice versa. Nothing separates him from the homies he encounters. That’s why he’s so genuine,” he said.

Debora is one of Clarke’s success stories. Debora went on to become a certified drug counselor and worked at Homeboy for more than a decade. A talented artist, he now runs art programs in prisons. Last year, Homeboy honored Debora at its annual dinner.

“I couldn’t be better,” said Debora. “I sit on my porch, and my kids are laughing and giggling. I look at the sky and say, ‘This is what it feels like to be a father, a homeowner, at peace.’ ”

Read More

Providing Strength in the Wake of Trauma

PAs’ Efforts to Help Homeless in LA Stymied by Outmoded Regulations

PA Leans In, Embraces Challenges, and Expands Care

Erasing the Past, Creating a Future (Long Beach Post)

Hillel Kuttler is a freelance writer and editor. He can be reached at [email protected].

Thank you for reading AAPA’s News Central

You have 2 articles left this month. Create a free account to read more stories, or become a member for more access to exclusive benefits! Already have an account? Log in.